|

By Science Outreach Intern Katrina McCollough

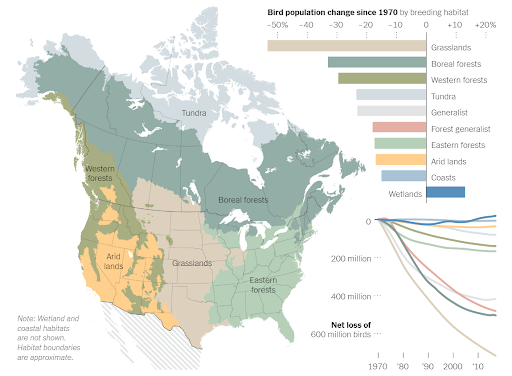

The word ‘migration’ describes periodic, large-scale movements of populations of animals. According to AllAboutBirds, “Birds migrate to move from areas of low or decreasing resources to areas of high or increasing resources.” The resources they are interested in are food and nesting locations. Not all birds migrate as far as Perry, some only migrate short distances like going up or down a mountain, others migrate a couple hundred miles. For long-distance migrants like Perry it’s common for them to move from their breeding ranges in the US and Canada, all the way down to their wintering homes in Central or South America. One of the birds Perry was modeled after was the Blackpoll Warblers which migrate up to 12,400 miles roundtrip each year, isn’t that incredible? And did you know that in preparation for winter migration, birds build fat reserves up to 40-60% of their body weight? This is their ‘energy storage’ for the long flight. Nonmigratory birds, on average, maintain a “fat load” of 3-5%, that’s a big difference! And they load up only two to three weeks before heading south. (photo by Nick Fewings) Perry is unique (and somewhat inaccurate) in that he did this migration alone, most birds are gregarious, meaning they enjoy company during migration (even ones that are usually solitary). Most people are familiar with the ‘flying V’s’ of geese, but smaller birds tend to flock in even larger numbers when they migrate. Have you ever seen a giant flock of birds overhead, making beautiful shapes in the sky? This is called a murmuration and it is one of the most awe-inspiring events you can experience. Check out this amazing video of kayakers catching a murmuration of Starlings above a lake. We know that the Blackpoll Warblers are incredible little migrators, but the bird world is full of many impressive fliers. Hummingbirds are the smallest migrating bird, at just an eighth of an ounce they can travel up to 30 miles an hour when they migrate across the Gulf of Mexico, a 600-mile journey. The Bar-tailed Godwit holds the record for the longest nonstop flight, 6,800 miles from Alaska to New Zealand. The Wandering Albatross doesn’t technically count as a migrating bird simply because it is almost always on the move (wandering, get it?), circling the Southern Hemisphere’s oceans. It can fly up to 18,000 miles between breedings. America’s Blue Grouse has the shortest migration, checking in at just under 1,000 feet, and the Bar-headed Goose is the highest-flying bird, crossing the Himalayas and reaching altitudes up to 23,000 feet. Even some species of penguins migrate proving you don’t always need to fly to get where you need to go. Is anyone feeling a little lazy after reading about these little guys? (photo by David Cousins) How do birds navigate during migration? Full disclosure! Scientists don’t know 100% of everything about birds' amazing navigational skills, but they’ve figured a few things out. Birds use several of their senses when migrating. They can get compass information from the sun and stars by sensing the Earth’s magnetic field, and they get information from the position of the setting sun and other various landmarks that they see. There’s also evidence that some birds, including homing pigeons, use their sense of smell. A lot of waterfowl and cranes follow pathways related to important stopover locations, places they can eat and rest. What’s happening to migrating bird populations? AllAboutBirds sums up the issue well, “Taking a journey that can stretch to a round-trip distance of several thousand miles is a dangerous and arduous undertaking. It is an effort that tests both the birds’ physical and mental capabilities. The physical stress of the trip, lack of adequate food supplies along the way, bad weather, and increased exposure to predators all add to the hazards of the journey. In recent decades long-distance migrants have been facing a growing threat from communication towers and tall buildings. Many species are attracted to the lights of tall buildings and millions are killed each year in collisions with the structures.” (Graph from New York Times) One major cause of the decline in migratory populations is climate change caused by global warming. Climate change leads to changes and shifts in habitats, which can cause the redistribution of birds, and in some cases a nearly complete loss of their habitats. Flying long distances involves crossing many borders between countries with varying environmental politics, legislation and conservation measures. It’s really important to have international cooperation among governments, NGOs and other stakeholders share knowledge and coordinate conservation efforts. Did you notice when Perry crossed the border into Mexico, then the US, then Canada? Neither did he! We humans have made these boundaries but the birds aren’t a part of that. It’s up to us to cooperate across state and international lines to protect the birds that migrate through our areas. Support international organizations that support migration corridors, migration hotspots, and any other bird conservation efforts. Every person can make a difference, whether in your community or in the world. For more information on national projects that are focused on conservation measures you can check out the US Fish and Wildlife Service’s page on Conservation Measures The Mission of Perry's Journey - A Message from the Illustrator It’s important we understand that just because birds can fly over it all, doesn’t mean they aren’t affected by what’s going on down here on the ground. The population of North American birds has dropped by nearly 30% since the 1970s, that is a total of almost 3 billion birds. Gone. Birds are incredibly important to the balance of our ecosystems: they are essential as pollinators and for seed dispersal, particularly for native plants, and they feed on and help control a variety of critters we consider pests like insects and rodents. Bird studies teach us about climate and the environment, and the birds themselves are key indicators of environmental change. And, most simply, birds are beautiful, and they provide us with music and joy. The protagonist of this story, Perry, is doing his part as a bird, migrating to his northern breeding location to hopefully pass on his little brown bird genes. It’s all he can do. Perry’s Journey illustrates the important journey of birds like him across the globe, who are doing their parts to help. Migrating birds are disproportionately affected because they need not just one habitat, but multiple habitats that can serve as stopping points along their journeys. We call these migration corridors and it’s important that they are protected: for the birds’ sakes as well as our own. Birds like Perry can’t control what happens on the ground, or in the water and air, but we can. During Perry’s journey over the couse of ten posts, we will go into some of the main issues facing not just migrating birds, but all birds, and what you can do to help. To support SFBBO's work to conserve birds and their habitats through science and outreach, please make a donation to our Spring Appeal!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

WingbeatWingbeat is a blog where you can find the most recent stories about our science and outreach work. We'll also share guest posts from volunteers, donors, partners, and others in the avian science and conservation world. To be a guest writer, please contact [email protected]. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

San Francisco Bay Bird Observatory ● 524 Valley Way, Milpitas, CA 95035 ● 408-946-6548 ● [email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed