|

By Guest Blogger Dudley Carlson

southern California biologists who study condors, rescue injured ones, and explore the multiple threats to their existence. The survival of this largest of North American birds, whose population was once down to double digits, is due to the work of many scientists, from those who captured the last known birds in order to raise their offspring in zoos and return them to the wild, to those working today to track the progress of the increasing population and discover and remove the threats to its existence. These include lead shot, often ingested by condors eating carcasses killed by hunters or ranchers; micro-trash that can choke young birds; and wildfire, among others.

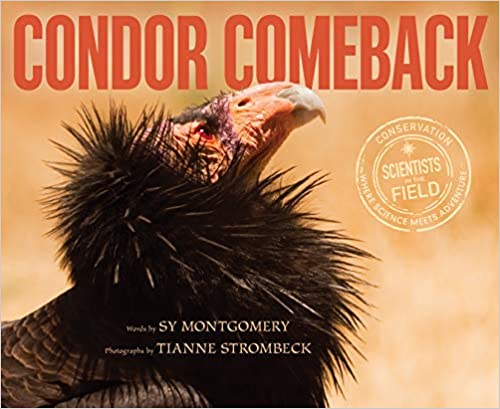

Numerous photos expand the text, showing condors being measured and tagged, carcasses being eaten, scientists holding and releasing the birds, and young birds in the nest. This is not easy work. Montgomery describes long hours in the field under blazing sun; hiking in desolate areas in search of missing birds; a chance pre-dawn encounter with a mountain lion; and the messy business of working with birds that eat carrion and often vomit it on anyone whom they perceive as a threat. But the rewards are enormous. From fewer than 25 remaining birds in 1982 and the capture of the last known wild bird in 1987 to the return of more than 450 today, California Condors have survived thanks to the intervention of scientists who have invested their careers in understanding this unusual bird in order to save it from extinction. Some of these scientists work in zoos, overseeing and caring for adult birds that are raising chicks from egg to hatchling to the age when they can be released into the wild, or teaching zoo visitors about threats to the birds and the challenges of preventing their extinction. Some spend many hours in the field, following condors that wear tracking devices or GPS locators, searching for those that go missing, rescuing those that become ill, and monitoring their health with yearly checkups and measurements. Still others work in the lab, studying condor DNA to learn more about them, examining their blood to help determine what makes them ill or kills them. It takes large teams of scientists and volunteers to make all this happen. Along with history of the condor’s decline and resurgence, Montgomery includes information about the reverence for vultures of all kinds in many world cultures, including those of Native American tribes. At the end of her text are multiple resource lists, from books, websites and webcams to curricula for teachers, organizations supporting condor rescue or research, and places to visit in order to see live condors. And with accompanying photos, she discusses the many ways condors are viewed, from the ugliest of birds to the most regally handsome. For middle-grade readers, here is a wealth of information about a singular bird and the wide variety of people who study, learn and teach about them and do research to promote their survival. For those stuck at home this winter, it’s a great way to learn, and a doorway to wonderful webcams for the next season of nesting. SFBBO member Dudley Carlson, a biologist’s daughter, grew up in a family of birders and was Manager of Youth Services at Princeton (NJ) Public Library for 25 years. She believes that if children enjoy learning about birds and understand how important they are to our environment, then birds, nature and people will have a better chance at a healthy future. You can see all of Dudley's book recommendations here.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

WingbeatWingbeat is a blog where you can find the most recent stories about our science and outreach work. We'll also share guest posts from volunteers, donors, partners, and others in the avian science and conservation world. To be a guest writer, please contact [email protected]. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

San Francisco Bay Bird Observatory ● 524 Valley Way, Milpitas, CA 95035 ● 408-946-6548 ● [email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed