Peer-Reviewed Research Papers Using Data From CCFS

For 40 years our scientists and community science volunteers have collected bird mist netting and bird banding data at our Coyote Creek Field Station (CCFS) in North San Jose, CA. Our scientists, as well as local university students and other scientists have used our data, and sometimes also access at the station, to learn about the status and behavior of our local birds, including understanding patterns in migration, social affiliation, and the impacts of climate change. To view summaries and links to PDFs of peer reviewed papers on this research, please click the plus sign (+) to the right of the paper title.

2023: A SIMPLE METHOD TO ESTIMATE CAPTURE HEIGHT BIASES AT LANDBIRD BANDING STATIONS: OPPORTUNITIES AND LIMITATIONS

A simple method to estimate capture height biases at landbird banding stations: Opportunities and limitations

Authors: D. Julian Tattoni, Katie LaBarbera

Published in: Journal of Field Ornithology (2023)

Summary: Mist nets are widely used to collect bird monitoring data. We know from our 2022 study that these data can be affected by capture height biases—where one species, or even subset of a species (one sex, one age group), differs in the height at which they are most active—because activity height affects the likelihood of capturing a bird with standard 3-meter-high mist nets. Understanding which species or groups exhibit capture height bias is important for mitigating the effect this has on the data. In the past, capture height bias has been studied using double-high mist nets, but these are expensive and difficult to build. In this paper we demonstrate that a much simpler method, which we piloted at CCFS, can yield information about many capture height biases without the need to build different net rigs.

Authors: D. Julian Tattoni, Katie LaBarbera

Published in: Journal of Field Ornithology (2023)

Summary: Mist nets are widely used to collect bird monitoring data. We know from our 2022 study that these data can be affected by capture height biases—where one species, or even subset of a species (one sex, one age group), differs in the height at which they are most active—because activity height affects the likelihood of capturing a bird with standard 3-meter-high mist nets. Understanding which species or groups exhibit capture height bias is important for mitigating the effect this has on the data. In the past, capture height bias has been studied using double-high mist nets, but these are expensive and difficult to build. In this paper we demonstrate that a much simpler method, which we piloted at CCFS, can yield information about many capture height biases without the need to build different net rigs.

2022: LONG TERM PROgress in riparian restoration with concurrent avian declines in the southern san francisco bay area (ca)

|

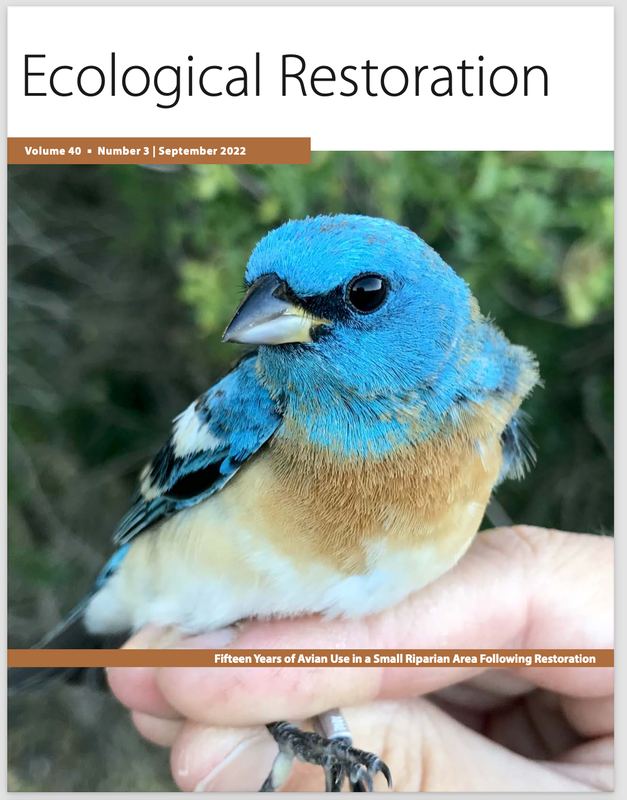

Long term progress in riparian restoration with concurrent avian declines in the southern San Francisco Bay Area (CA)

Authors: Iris T. Stewart, Liam Healey, Katie LaBarbera, Hongyu Li, Josh C. Scullen, Yiwei Wang, Dan Wenny Published in: Ecological Restoration (2022) This paper, a collaboration between SFBBO and Santa Clara University, investigates the long-term success of the restoration efforts that, in 1987 and 1993, aimed to turn pear orchard back into riparian woodland at Coyote Creek Field Station. The authors looked at both the botanical aspects of the restoration - measures like plant species diversity and tree size - as well as avian presence at the restored sites, to compare the restored sites to the remnant, never-destroyed riparian woodland. They found that the restored sites had become more similar to the remnant riparian site over time in both botanical and avian metrics, but never became indistinguishable, pointing to partial success of the restoration. The researchers also found that migrant bird species were declining over time in all habitats, which is a common pattern observed under climate change. This paper will be valuable for planning future restoration efforts. |

2022: INcidence and extent of eccentric preformative molt in the california and canyon towhees

Incidence and extent of eccentric preformative molt in the California and Canyon Towhees

Authors: D. Julian Tattoni, Katie LaBarbera, Charles D. Hathcock

Published in: Western Birds (2022)

Molting is an important, energetically-expensive stage of a bird’s life. Different groups of birds have different molt patterns, and there is growing evidence that molt strategies are linked to environmental conditions and can change as the environment changes. In this note, the researchers document a previously unreported pattern of molt in two species of towhees.

Authors: D. Julian Tattoni, Katie LaBarbera, Charles D. Hathcock

Published in: Western Birds (2022)

Molting is an important, energetically-expensive stage of a bird’s life. Different groups of birds have different molt patterns, and there is growing evidence that molt strategies are linked to environmental conditions and can change as the environment changes. In this note, the researchers document a previously unreported pattern of molt in two species of towhees.

2022: CAPTURE HEIGHT BIASES FOR BIRDS IN MIST-NETS VARY BY TAXON, SEASON, AND FORAGING GUILD IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA

Capture height biases for birds in mist-nets vary by taxon, season, and foraging guild in northern California

Authors: D. Julian Tattoni, Katie LaBarbera

Published in: Journal of Field Ornithology (2022)

Summary: Mist-nets are the standard bird capture method for studying a wide range of questions about bird populations. Mist-nets are almost always deployed such that their maximum height is no higher than three meters. Since we know that birds often fly higher than three meters, this raises a concern: could missing these higher-flying birds bias the results of studies that use standard mist-net methods? For example, if a project was monitoring the ratio of males to females in a population, but in that species females flew higher than males, the mist-nets might be less likely to capture females than males and could yield an incorrect sex ratio estimate. Analyzing 27 years of capture data from CCFS’ double-high nets, which consist of a standard-level net with a second, higher-level net stacked above it, Tattoni and LaBarbera found that 20 of 43 bird taxa had a bias toward capture in the lower or the higher net. Five taxa showed seasonal differences in their capture height bias. Effects of sex, age, and capture history on capture height bias were present but rare. Further study on capture height bias as it relates to season and habitat would be valuable, and researchers using mist nets should consider whether their research question is vulnerable to being impacted by capture height bias.

Authors: D. Julian Tattoni, Katie LaBarbera

Published in: Journal of Field Ornithology (2022)

Summary: Mist-nets are the standard bird capture method for studying a wide range of questions about bird populations. Mist-nets are almost always deployed such that their maximum height is no higher than three meters. Since we know that birds often fly higher than three meters, this raises a concern: could missing these higher-flying birds bias the results of studies that use standard mist-net methods? For example, if a project was monitoring the ratio of males to females in a population, but in that species females flew higher than males, the mist-nets might be less likely to capture females than males and could yield an incorrect sex ratio estimate. Analyzing 27 years of capture data from CCFS’ double-high nets, which consist of a standard-level net with a second, higher-level net stacked above it, Tattoni and LaBarbera found that 20 of 43 bird taxa had a bias toward capture in the lower or the higher net. Five taxa showed seasonal differences in their capture height bias. Effects of sex, age, and capture history on capture height bias were present but rare. Further study on capture height bias as it relates to season and habitat would be valuable, and researchers using mist nets should consider whether their research question is vulnerable to being impacted by capture height bias.

2021: using individual capture data to reveal large-scale patterns of social association in birds

|

Using individual capture data to reveal large-scale patterns of social association in birds (PDF)

Authors: Katie LaBarbera, Josh C. Scullen Published in: Journal of Ornithology (2021) Summary: Animal social behavior—who animals associate with and how often—can shed light on the challenges they face, such as avoiding predators, finding food, and finding a mate. Social behavior is difficult to measure, however, as it requires a lot of time (for observers to watch the animals) or money (to fund technology that can automatically “observe”). While banding birds at CCFS, Dr. Katie LaBarbera noticed that they often caught flocks of birds all together, and wondered whether banding data could provide a glimpse into bird social behavior. LaBarbera and Josh Scullen, SFBBO’s then-Landbird Director, used social network analysis of CCFS’ banding data from 1996-2018 to detect patterns of social association related to age and taxon for the six most-captured species at CCFS. For example, they found that the two subspecies of White-crowned Sparrow associated more often within their own subspecies than with the other subspecies, despite both living in the same wintering area at CCFS. Additional analyses with computer simulations lend confidence that these patterns are reflecting real bird behavior, not simply “noise” in the banding data. The authors hope that this study will encourage more analyses of the social patterns in bird banding data, since bird banding data already exist for many species and over long time periods, providing a great opportunity for insights into bird social behavior. |

2017: LONG-TERM CHANGES IN THE SEASONAL TIMING OF LANDBIRD MIGRATION ON THE PACIFIC FLYWAY

Long-term changes in the seasonal timing of landbird migration on the Pacific Flyway (PDF)

Authors: Gina G. Barton, Brett K. Sandercock

Published in: The Condor (2017)

Summary - The timing of life events, technically termed “phenology,” is one of the main things that scientists expect to shift as large-scale changes, such as those caused by climate change, affect the world. The timing of bird migration is extremely important to the health of migratory species, because a mis-timed migration can mean arriving to the breeding grounds too late to catch the burst of spring caterpillars that chicks need to grow big, or getting caught in a deadly snowstorm. Gina Barton and Dr. Brett Sandercock looked at CCFS banding records for five migrant species from 1987-2008 and found that all of them had shifted their migration timing, but that these shifts varied among species, with some species shifting to a longer migration period while others’ migration periods were compressed. They also found that regional climatic conditions like El Niño affected migration timing in short-distance migrants more than in long-distance migrants. Studies such as this one depend upon long-term datasets like the one at CCFS.

Authors: Gina G. Barton, Brett K. Sandercock

Published in: The Condor (2017)

Summary - The timing of life events, technically termed “phenology,” is one of the main things that scientists expect to shift as large-scale changes, such as those caused by climate change, affect the world. The timing of bird migration is extremely important to the health of migratory species, because a mis-timed migration can mean arriving to the breeding grounds too late to catch the burst of spring caterpillars that chicks need to grow big, or getting caught in a deadly snowstorm. Gina Barton and Dr. Brett Sandercock looked at CCFS banding records for five migrant species from 1987-2008 and found that all of them had shifted their migration timing, but that these shifts varied among species, with some species shifting to a longer migration period while others’ migration periods were compressed. They also found that regional climatic conditions like El Niño affected migration timing in short-distance migrants more than in long-distance migrants. Studies such as this one depend upon long-term datasets like the one at CCFS.

2016: MIGRATION PATTERNS OF SF BAY AREA HERMIT THRUSHES DIFFER ACROSS A FINE SPATIAL SCALE

|

Migration patterns of San Francisco Bay Area Hermit Thrushes

differ across a fine spatial scale (PDF) Authors: Allison R. Nelson, Renée L. Cormier, Diana L. Humple, Josh C. Scullen, Ravinder Sehgal, Nathaniel E. Seavy Published in: Animal Migration (2016) Summary - Dr. Allison Nelson and colleagues used a new, especially light-weight tracking technology called the light-level geolocator to track the migration of Hermit Thrushes wintering in the San Francisco Bay. They attached small geolocator tags to 32 birds, and the following year they recaptured ten of those birds and were able to read the data stored in their tags. They found that Hermit Thrushes wintering in the south bay (captured and banded at CCFS) had breeding territories further north along the coast of British Columbia than most of the Hermit Thrushes wintering in the north bay. This work demonstrated that birds can differ in migratory behavior even over small geographic distances. As part of this study the researchers genetically determined the sex of Hermit Thrushes wintering in the Bay, and they unexpectedly found that our wintering Hermit Thrushes have a female:male sex ratio of 3:1! |

2012: HOW SAFE IS MIST NETTING?

How safe is mist netting? Evaluating the risk of injury and mortality to birds (PDF)

Authors: Erica N. Spotswood, Kari Roesch Goodman, Jay Carlisle, Renée L. Cormier, Diana L. Humple, Josée Rousseau, Susan L. Guers, Gina G. Barton

Published in: Methods in Ecology and Evolution (2012)

Summary - Dr. Erica Spotswood and colleagues used data from 22 banding stations, including CCFS, to ask: how safe is mist netting for the birds? They looked at the frequency of injuries and deaths during capture and banding, as well as the survival rates of birds after they were injured. They found that rates of injury and death were extremely low (less than 0.6%), and that injury did not appear to reduce a bird’s chances of survival. They also identified differences in species’ susceptibility to different injuries. Knowledge of these patterns can help banders prepare for and reduce the chances of these injuries. However, the data in this study reflect conditions at only some banding stations: the authors contacted 70 banding organizations, and only 22 (including CCFS) provided data. We urge all banding stations to avoid complacency and always look for new ways to keep birds safer.

Authors: Erica N. Spotswood, Kari Roesch Goodman, Jay Carlisle, Renée L. Cormier, Diana L. Humple, Josée Rousseau, Susan L. Guers, Gina G. Barton

Published in: Methods in Ecology and Evolution (2012)

Summary - Dr. Erica Spotswood and colleagues used data from 22 banding stations, including CCFS, to ask: how safe is mist netting for the birds? They looked at the frequency of injuries and deaths during capture and banding, as well as the survival rates of birds after they were injured. They found that rates of injury and death were extremely low (less than 0.6%), and that injury did not appear to reduce a bird’s chances of survival. They also identified differences in species’ susceptibility to different injuries. Knowledge of these patterns can help banders prepare for and reduce the chances of these injuries. However, the data in this study reflect conditions at only some banding stations: the authors contacted 70 banding organizations, and only 22 (including CCFS) provided data. We urge all banding stations to avoid complacency and always look for new ways to keep birds safer.

2012: AVIAN BODY SIZE CHANGES AND CLIMATE CHANGE: WARMING OR INCREASING VARIABILITY?

Avian body size changes and climate change: warming or increasing variability? (PDF)

Authors: Rae E. Goodman, Gretchen Lebuhn, Nathaniel E. Seavy, Thomas Gardali, Jill D. Bluso‐Demers

Published in: Global Change Biology (2012)

Researchers used CCFS data from 1983-2009 as well as data from the Palomarin banding station in Marin Co. from 1971-2010 to investigate whether bird size (body mass and wing length) has been changing over time. After analyzing measurements from 18,052 individual birds from CCFS and 14,735 individual birds from Palomarin, they found that wing length has been steadily increasing over time at a rate of approximately 0.05% per year. Body mass was more variable among species and seasons, but generally also increased. These results are opposite to those observed in Pennsylvania birds, which have decreased in size over time. Taken together, these patterns suggest that birds are changing in size over time, but that the drivers of that change probably vary geographically. The researchers suggest that while birds in Pennsylvania may be shrinking for better temperature regulation in a warming climate (a relationship known among ecologists as “Bergmann’s Rule”), California birds may be growing in size to better handle the increasing variability brought about by climate change.

Authors: Rae E. Goodman, Gretchen Lebuhn, Nathaniel E. Seavy, Thomas Gardali, Jill D. Bluso‐Demers

Published in: Global Change Biology (2012)

Researchers used CCFS data from 1983-2009 as well as data from the Palomarin banding station in Marin Co. from 1971-2010 to investigate whether bird size (body mass and wing length) has been changing over time. After analyzing measurements from 18,052 individual birds from CCFS and 14,735 individual birds from Palomarin, they found that wing length has been steadily increasing over time at a rate of approximately 0.05% per year. Body mass was more variable among species and seasons, but generally also increased. These results are opposite to those observed in Pennsylvania birds, which have decreased in size over time. Taken together, these patterns suggest that birds are changing in size over time, but that the drivers of that change probably vary geographically. The researchers suggest that while birds in Pennsylvania may be shrinking for better temperature regulation in a warming climate (a relationship known among ecologists as “Bergmann’s Rule”), California birds may be growing in size to better handle the increasing variability brought about by climate change.

2002: ANNUAL SURVIVAL RATES OF WINTERING SPARROWS: ASSESSING DEMOGRAPHIC CONSEQUENCES OF MIGRATION

|

Annual survival rates of wintering sparrows:

assessing demographic consequences of migration (PDF) Authors: Brett K. Sandercock, Alvaro Jaramillo Published in: The Auk (2002) Summary - The authors used CCFS data from 1985-1997 to estimate survival rates of wintering sparrows. They studied “local survival,” meaning that their survival rate is a combination of true survival and of site fidelity: a bird that is alive but has traveled somewhere else will not be detected at CCFS, and therefore will not be considered to have “survived” in a local-to-CCFS sense. The researchers’ estimated local survival rates ranged from a low of 0.35 (Fox Sparrow) to a high of 0.56 (Song Sparrow). Surprisingly, although migration is thought to be dangerous, they found no relationship between survival rate and migratory behavior or migratory distance. |

1994: SEXUAL DIFFERENCES IN SPRING MIGRATION OF ORANGE-CROWNED WARBLERS

Sexual differences in spring migration of Orange-crowned Warblers

Author: Christopher D. Otahal

Published in: North American Bird Bander (1994)

Otahal compared the timing of spring migration of male and female Orange-crowned Warblers through CCFS on their way north to their breeding grounds using banding data from six spring seasons (1988-1993). Although there was overlap in the timing of migration between males and females, the peak of migration was consistently earlier in males than in females. This may be because males that arrive to the breeding grounds early get to claim the better territories, while females do not need to claim territories.

Author: Christopher D. Otahal

Published in: North American Bird Bander (1994)

Otahal compared the timing of spring migration of male and female Orange-crowned Warblers through CCFS on their way north to their breeding grounds using banding data from six spring seasons (1988-1993). Although there was overlap in the timing of migration between males and females, the peak of migration was consistently earlier in males than in females. This may be because males that arrive to the breeding grounds early get to claim the better territories, while females do not need to claim territories.