In March 2020, we started Ask A Scientist on our social media where we covered a different topic each week and invited people to ask questions. Click the topics below to learn more about them, then click the images on the right to see a few of the questions and answers we received!

California Least Terns

|

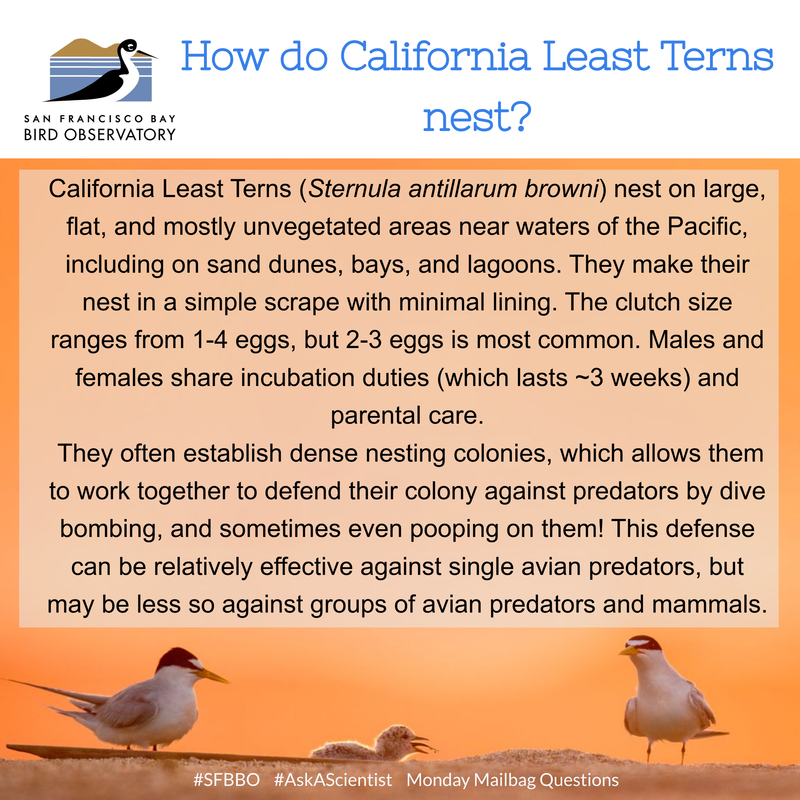

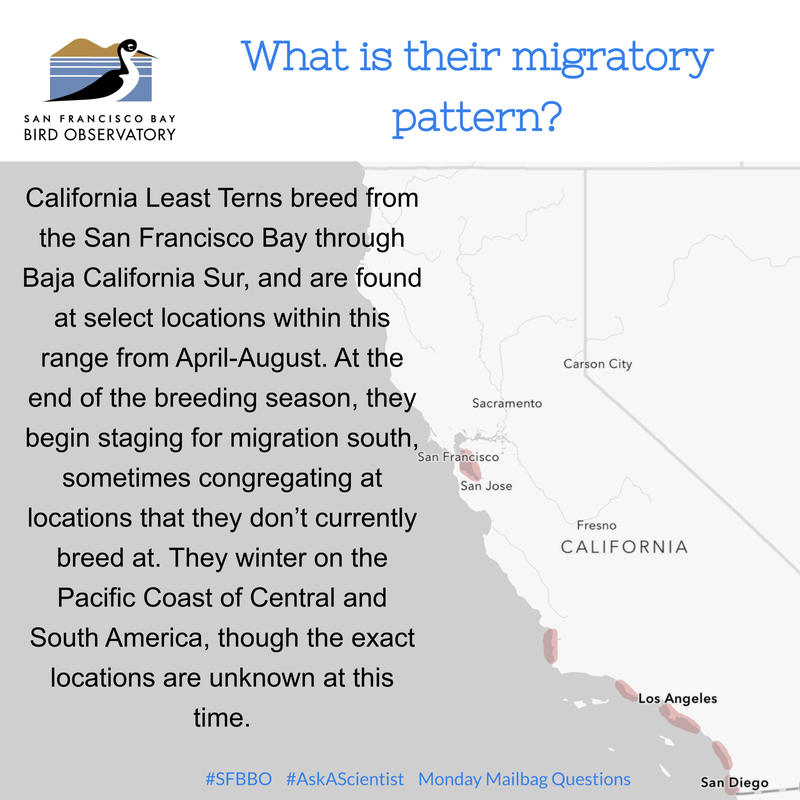

The endangered California Least Tern ranges from the Bay Area to the tip of Baja California. Historically, there were no breeding Least Terns in the San Francisco Bay except Monterey, but the creation of salt ponds provided suitable breeding habitat for them. We monitor a colony in Eden Landing - one of only 5 colonies in Northern California!

In March 2020, volunteers helped us place tern decoys at Eden Landing. The goal is to attract more endangered California Least Terns and encourage them to nest and form colonies at the site. This technique is called social attraction. |

Thanks to SFBBO Plover & Tern Program Director Ben Pearl for answering these questions.

|

California Gulls

|

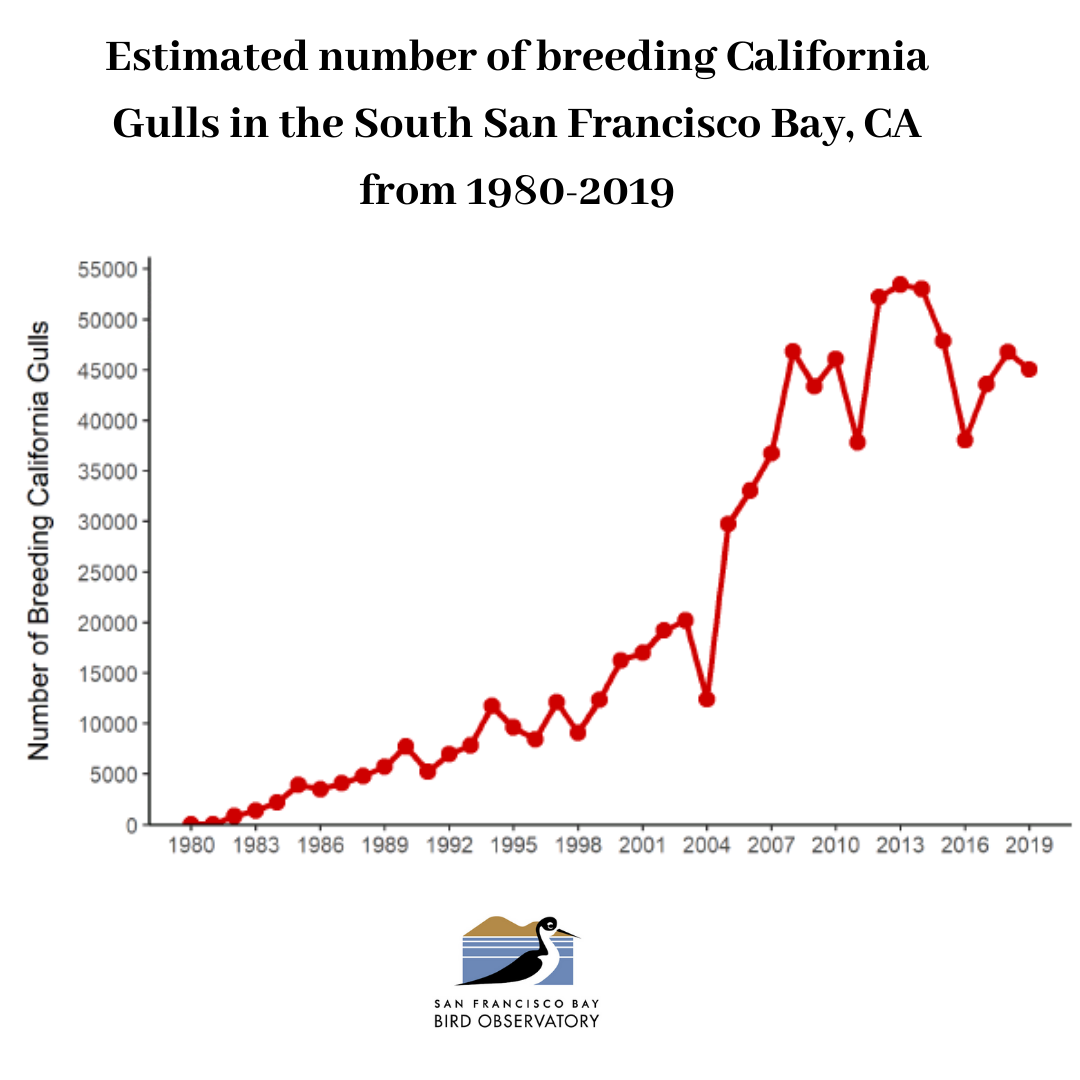

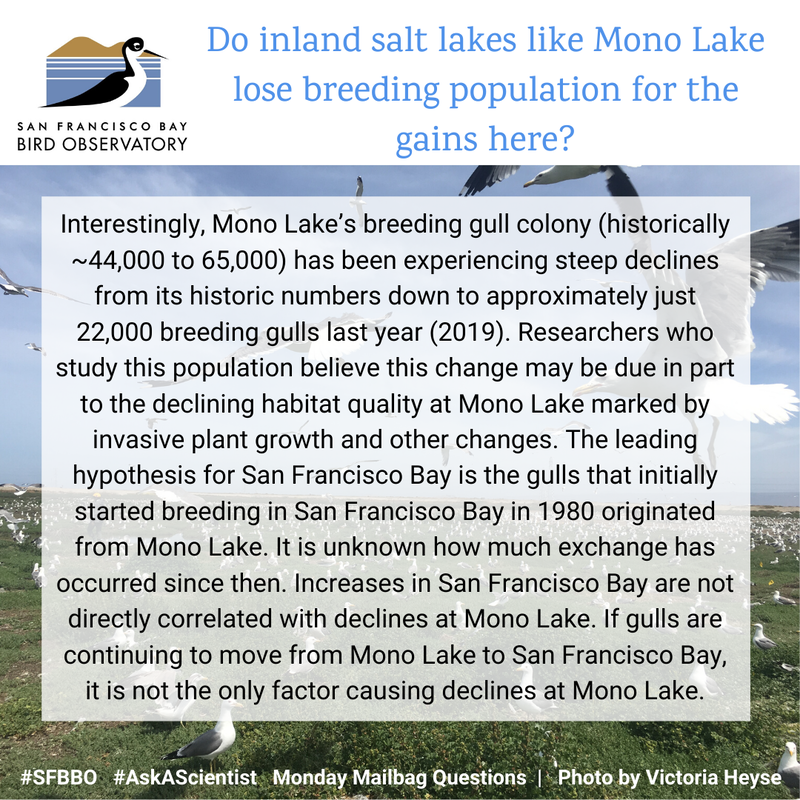

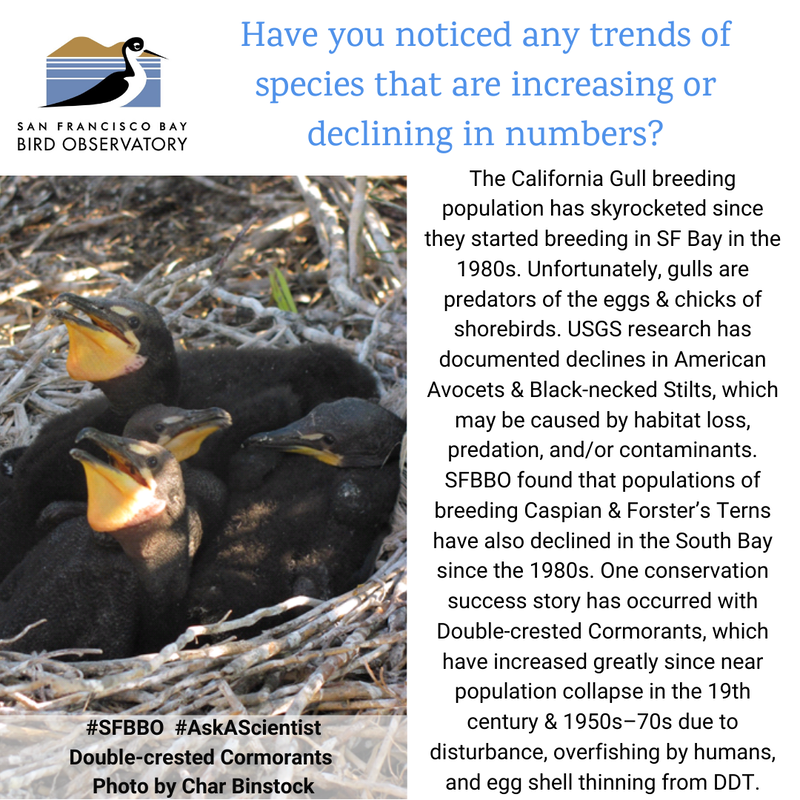

Did you know that California Gulls did not breed in San Francisco Bay until 1980? Prior to that, they only bred inland at saline lakes like Mono Lake. Now nearly 50,000 California Gulls come to breed in San Francisco Bay every spring. This will be SFBBO’s 40th year monitoring their population growth and movements.

These birds are predators and can eat the eggs and chicks of shorebirds like threatened Western Snowy Plovers, which is why monitoring their breeding is so important. Want to hear more about the impact of gulls and the work that SFBBO is doing? Check out this KALW radio story that featured California Gulls at Mono Lake and San Francisco Bay. |

Thanks to SFBBO's Waterbird team for answering these questions.

|

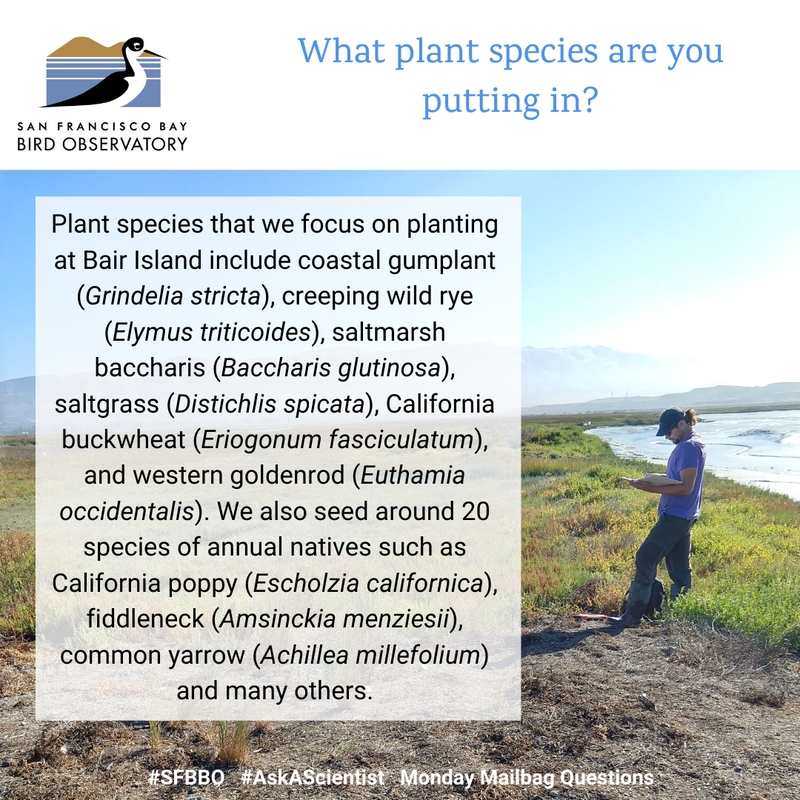

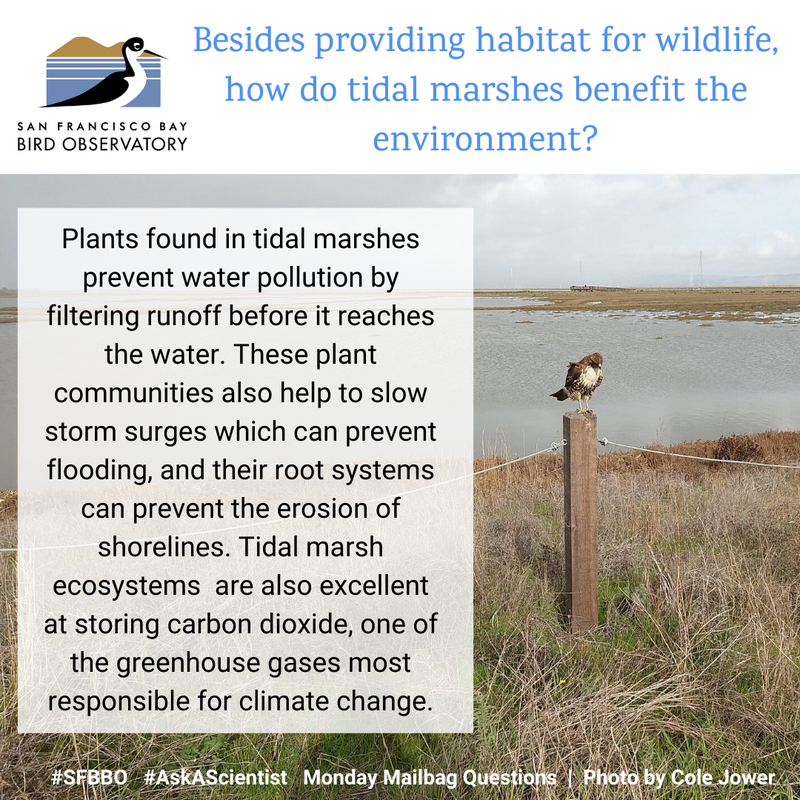

Habitat restoration

|

The transition zone between tidal marshes and upland areas is an ecosystem that many types of wildlife rely on, but much of it has been wiped out by urbanization in the Bay Area. SFBBO has been working to restore plant communities in these areas for nearly a decade.

Invasive plants are an ongoing problem in many of our restoration sites because they often out-compete natives and reduce biodiversity. One of our goals is to promote a plant community that is not only abundant, but diverse. To track this goal, SFBBO’s Habitats team conducts seasonal plant phenology surveys at our restoration sites. If you’d like to stay involved, keep an eye out for our photo spots along the trail at the Bair Island Wildlife Refuge in Redwood City. You can help us track plant community progression by taking pictures at these signs and sharing with us on social media. Thanks to SFBBO's Habitats team for answering these questions. |

|

Bird Banding

|

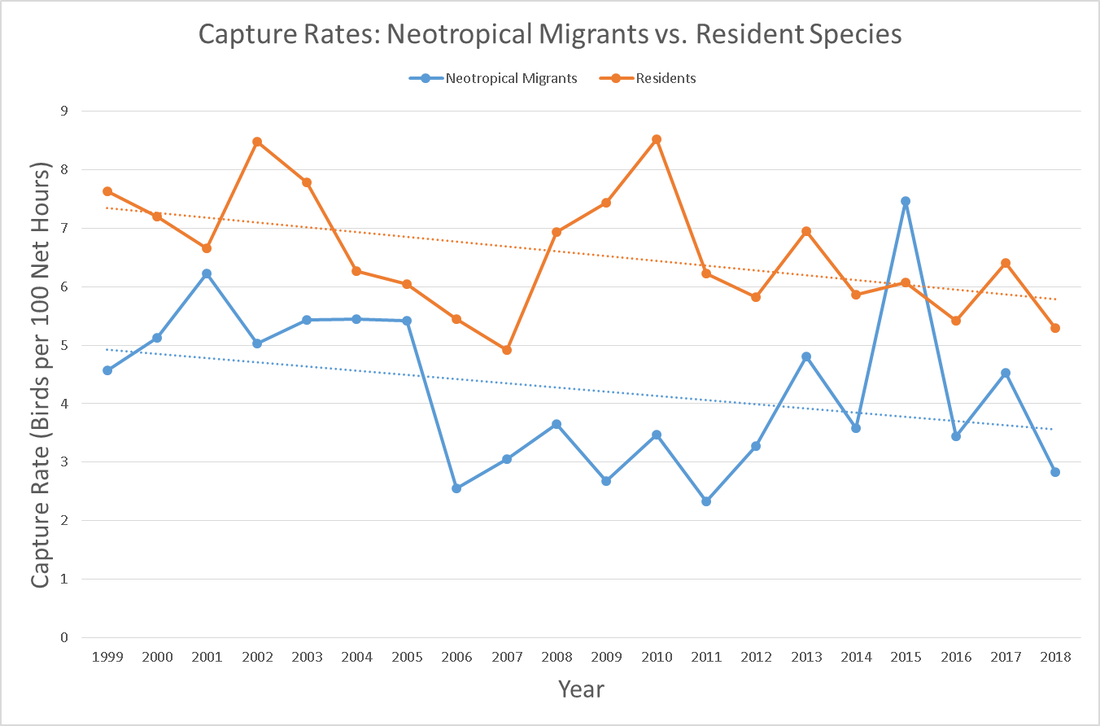

Did you know that SFBBO runs one of the few year-round bird banding stations in the US? We band about 2,500 birds per year with unique ID tags that identify individuals when we recapture them. We can use this data to look at population trends and life history patterns of resident and migratory species over time. Some of our tagged birds have lived 11 years!

SFBBO uses banding data from the Coyote Creek Field Station to track population trends over time. For a 20-year period between 1999 and 2018, bird populations on average have been declining. This graph shows two population groups: resident species like the Song Sparrow and Common Yellowthroat, and neotropical migrant species like the Yellow Warbler and Wilson's Warbler. Both populations groups are declining at similar rates, despite one group (residents) staying in the Bay Area year-round, and the other group (neotropical migrants) traveling hundreds of miles to winter in Central and South America. |

Thanks to SFBBO Landbird Program Director Josh Scullen for answering these questions.

|

Snowy plovers

|

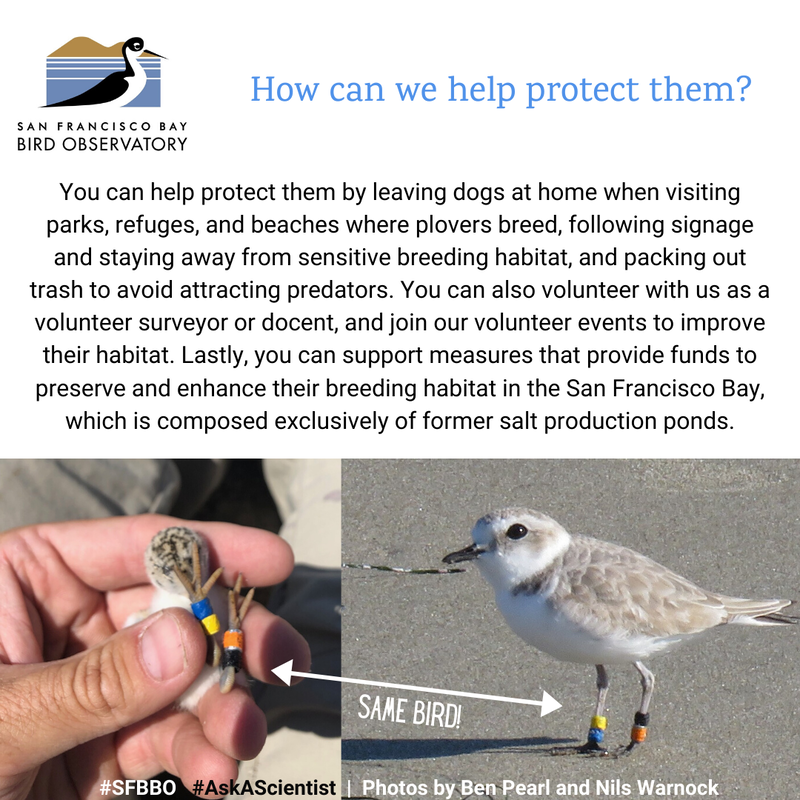

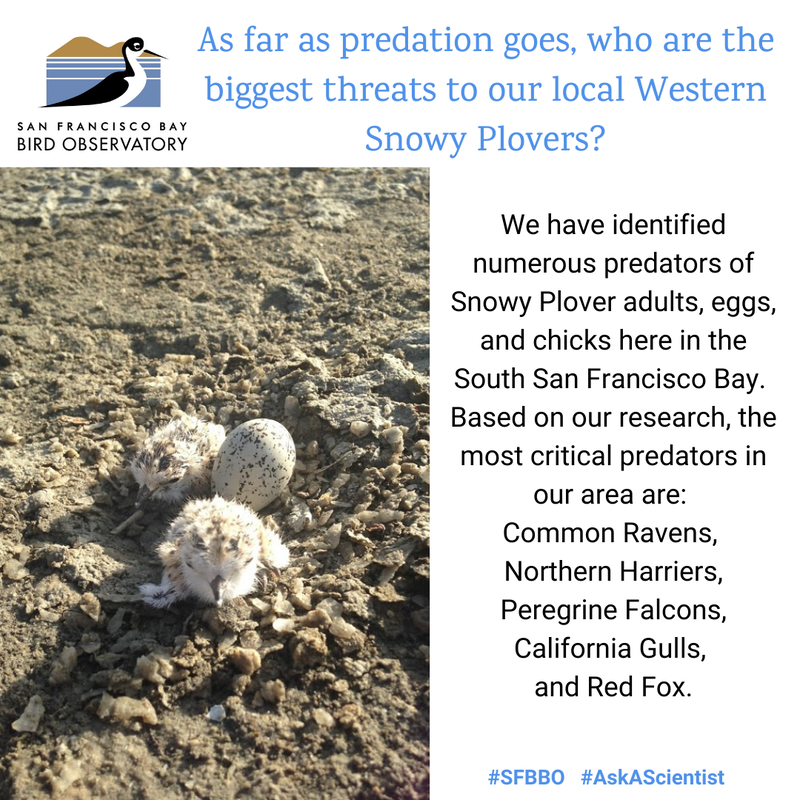

Since 2003, SFBBO has been monitoring these small ground-nesting shorebirds in the South Bay, where most Snowy Plovers in the San Francisco Bay are found. The Pacific Coast Population has been listed as a Federally Threatened “Distinct Population Segment” since 1993 due to habitat loss, human disturbance, and predation. The SF Bay population has averaged ~200 adults in recent years (almost 10% of the entire Pacific Coast Population). Fun fact: Snowy Plovers are polyandrous; males and females share incubation duties, yet males raise the chicks while the female starts a second nest with another male!

Snowy Plovers lay eggs directly on the ground in lined scrapes, so camouflage is important for nest success. Snowy Plovers select nest sites with oyster shells, which provide camouflage for adults, eggs, and chicks. Past SFBBO research has indicated that nest success may also improve when Snowy Plovers nest within Least Tern colonies, likely because Least Terns aggressively defend their colony from predators. SFBBO works closely with partners such as the US Fish & Wildlife Service to provide high quality habitat for both of these imperiled species! If you want to help threatened Western Snowy Plovers, keep an eye out for our next Mud Stomp habitat enhancement event! |

Thanks to SFBBO Plover & Tern Program Director Ben Pearl for answering these questions.

|

Colonial Waterbirds

|

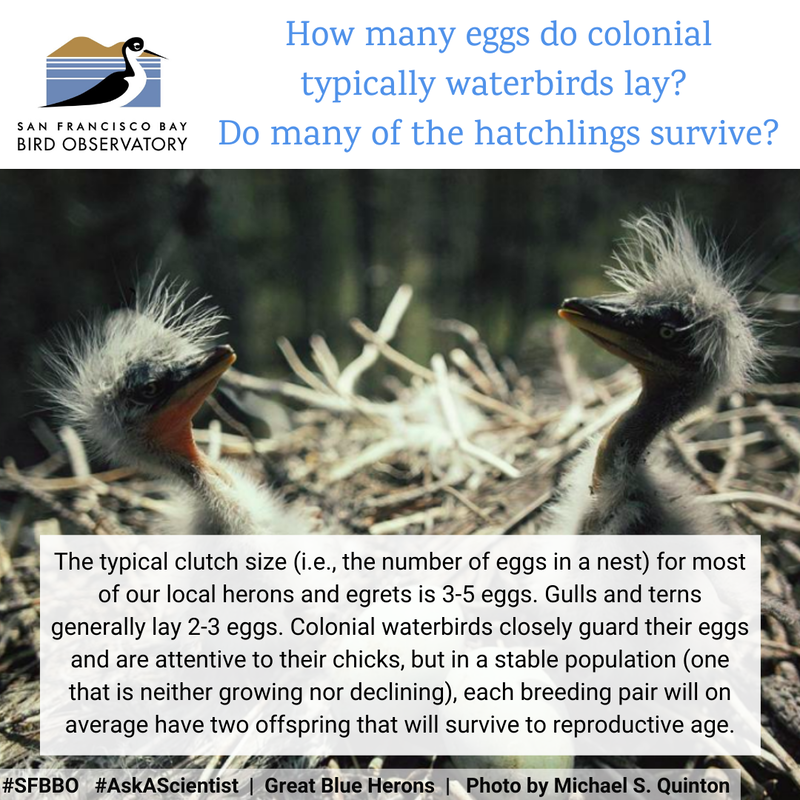

What is a “colonial waterbird”? These are birds that feed or live on the water and breed in groups called colonies. Colonies can include one or multiple species. We have many types of colonial waterbirds in San Francisco Bay, including herons, egrets, cormorants, terns, gulls, and shorebirds. April-June are the peak of the breeding season, so it’s a great time to learn more about our local colonies!

SFBBO’s Colonial Waterbird Monitoring Program has been tracking the nesting behaviors of colonial waterbirds since the 1980s - all thanks to the efforts of citizen scientists. Volunteers adopt colonies to monitor throughout the season and the data they collect help land managers to protect habitats for birds and people. Some of our volunteers have been monitoring the same colony for over 20 years! SFBBO monitors colonial waterbird colonies all around the Bay Area at a variety of sites. Some of the colonies are in more remote areas, but some of them nest in more urban habitats - including a colony in downtown Oakland! |

Thanks to SFBBO's Waterbird team for answering these questions.

|

Habitat Gardening

|

Urban development of the Bay Area has caused historically widespread habitats to be fragmented into smaller separated areas. As these areas shrink, the resources needed to support native animals are depleted, causing population declines and increased stress on ecosystems. Fortunately, there are ways for us to help - native gardens can help alleviate the loss of habitat by providing small areas of respite for the animals that need it most.

Here are some California native plants for your backyard bird sanctuary: 1. Pink flowering currant (Ribes sanguineum var. glutinosum) is a shrub that draws in hummingbirds with its flowers and attracts thrushes, quail, towhees, robins, and finches with its berries. 2. Twinberry (Lonicera involucrata) is a shrub that attracts hummingbirds when blossoming and robins, Wrentits, towhees, thrushes, Western Bluebird, and Chestnut-backed Chickadee when fruiting. 3. *Habitat Ecologist favorite* California sagebrush (Artemisia californica) is a shrub with delicate fragrant leaves that provides excellent shelter for birds. It is also known to attract Rufous-crowned Sparrows. |

Additional design features and tips for your habitat garden:

|

Hermit thrush migration

|

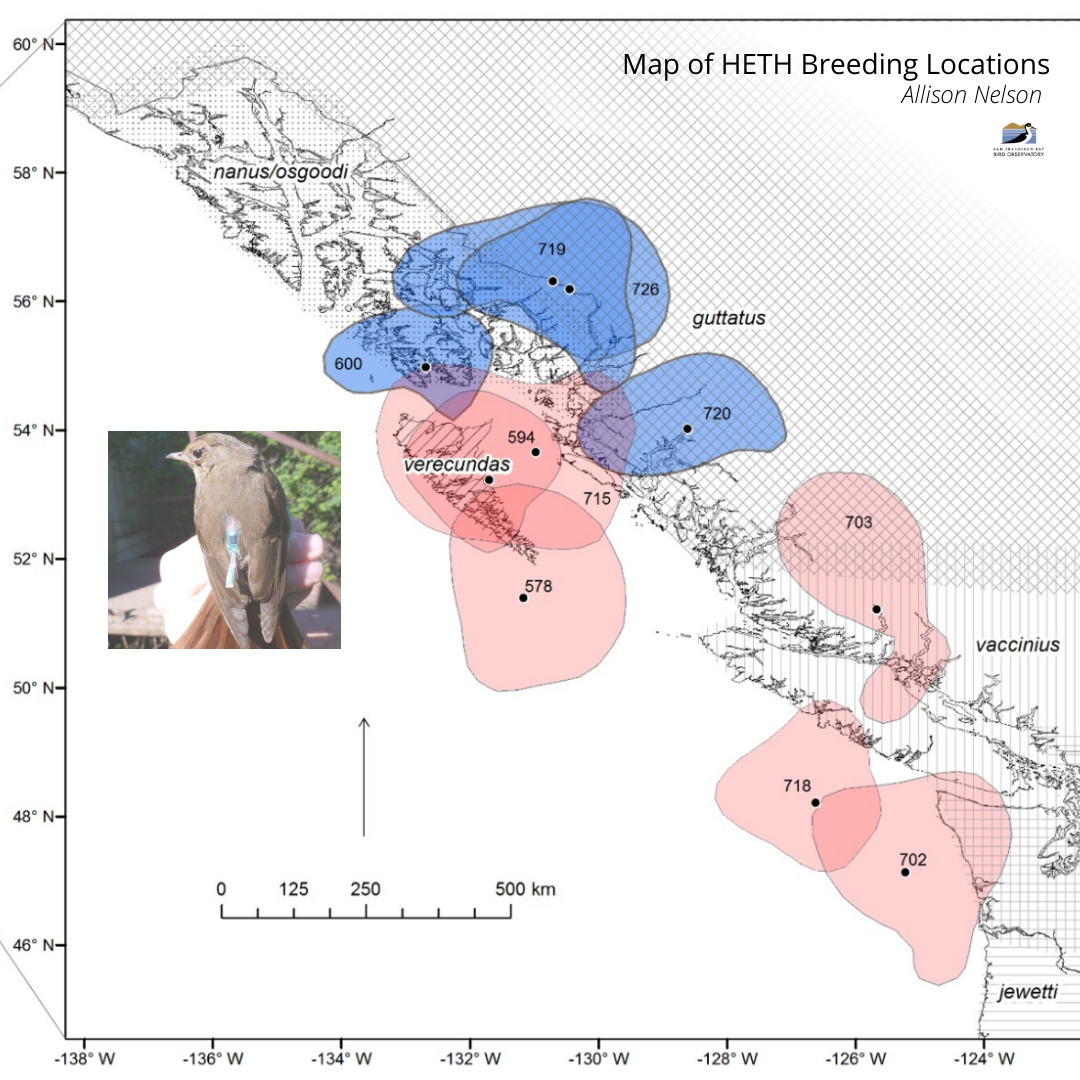

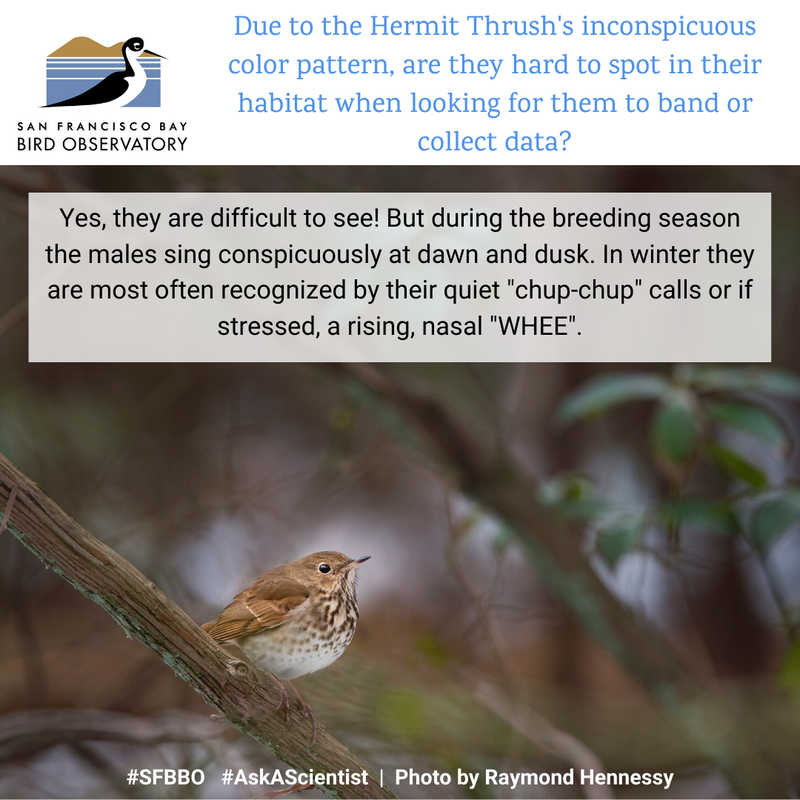

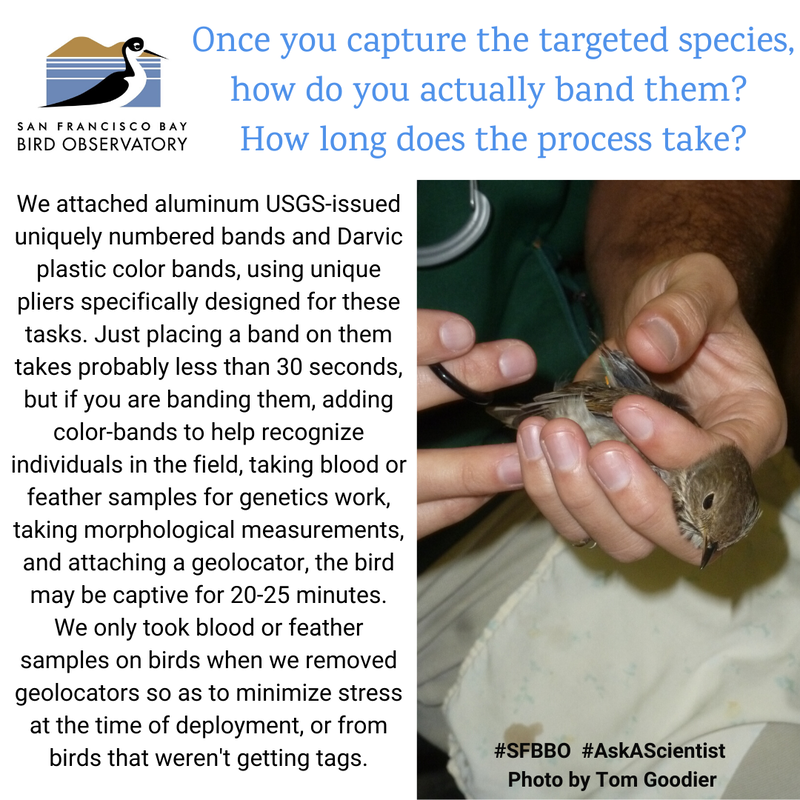

Hermit Thrushes are one of North America's favorite songbirds. Here in the Bay Area they are only winter visitors so we miss out on their lovely songs, which they save for their breeding grounds. In winter of 2012-2013 for her MS research, guest scientist Allison Nelson collaborated with SFBBO and Point Blue to deploy geolocators on Hermit Thrushes in Point Reyes and at CCFS to discover where these charismatic birds spend their summers.

She found a small-scale pattern of "leapfrog" migration in Hermit Thrushes, in which the southern (CCFS) wintering birds headed farther north than the northern (Point Blue) wintering birds. CCFS Hermit Thrushes migrated to the Alexander Archipelago of southeast Alaska and the adjacent British Columbia coast (shown in blue), and the Point Reyes birds migrated to sites farther south (shown in pink) near Vancouver Island, the island of Haida Gwaii, the British Columbia mainland, and the Olympic Peninsula of Washington |

Thanks to Allison Nelson for answering these questions. Allison was a banding volunteer at Coyote Creek Field Station while doing her MS at San Francisco State University. She is now the founder & director of Gold Country Avian Studies in Nevada City, CA.

|

Avian disease prevention program

|

SFBBO has been conducting surveys in the South Bay as a part of the Avian Disease Prevention Program since 1982. We survey Coyote Creek (also known as Artesian Slough) and Guadalupe Slough in search of sick, injured, or dead birds (and other wildlife including fish and sometimes even mammals), which we remove from the waters to prevent avian botulism. Some of our surveys are conducted from a truck driven on the levees, but most are conducted by boat with volunteers, who have helped us survey the South Bay waters for over 30 years!

Avian botulism is a disease found in birds caused by a toxin released by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. We most commonly find gulls affected with the disease, especially during warmer months. Infected birds often die of starvation or drowning caused by a gradual paralysis where they have difficulty diving, flying, and keeping their head up. Most birds that contract the disease will die of it, but early detection is a strong tool for prevention and some birds can survive if they receive treatment. Through our Avian Disease Prevention Program, SFBBO and volunteers work hard each year to prevent outbreaks by removing dead or sick birds and promoting healthy waterbird populations! |

Thanks to SFBBO Habitats Program Director Cole Jower for answering these questions.

|

Spiders

|

Spiders are an important part of the ecosystem; many are keystone predators and a food source for birds and other animals.

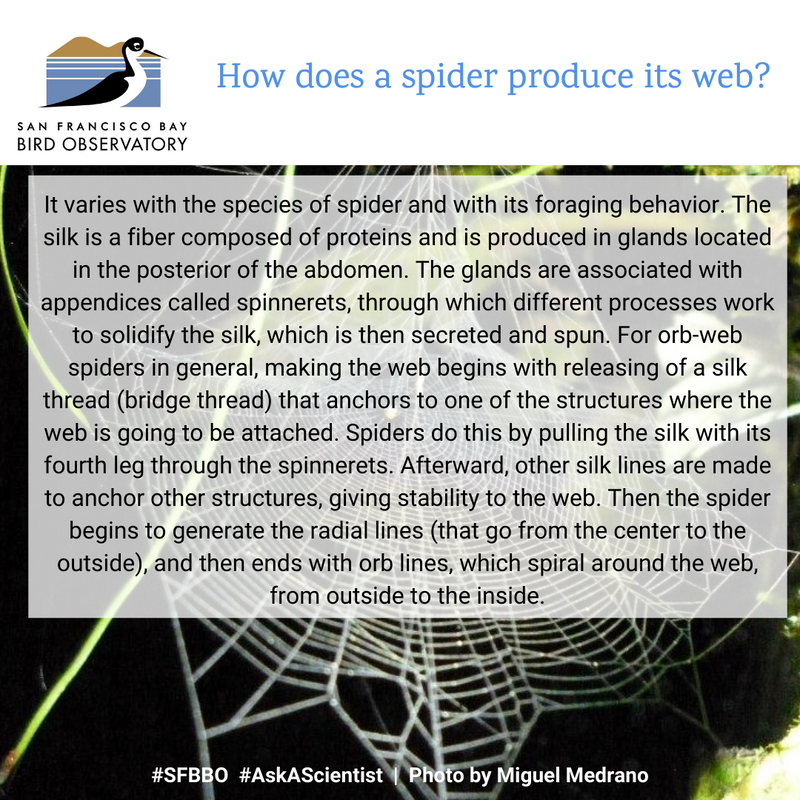

In the transition zone between tidal marshes and upland areas, we can find: orb-weavers that construct elaborate webs between vegetation; funnel-web and cobweb spiders that construct sheet webs in soil or low in vegetation; and wolf spiders, sac spiders, ground spiders, and jumping spiders, which live under rocks and other debris. Spiders produce silk made of proteins that are in liquid form within silk glands and solidify as the spider extracts it through spinnerets, specialized structures used to spin silk. Mixing of different types of threads allows spiders to create different kinds of silk used for various purposes, such as adding sticky droplets to make “capturing lines” in webs, transmitting vibration, dispersing, or wrapping fresh prey. Some birds incorporate spider web fibers into their nests, where the webs may serve a structural role, attaching nest materials together or with surroundings. Webs may also serve as an insulator in the internal lining of the nest, or as a thermoregulator, reflecting solar radiation when it covers the exterior of the nest. |

Thanks to SFBBO Ecologist Yeimy Cifuentes for answering these questions. She studied tarantulas in Colombia.

|

Burrowing owls

|

Did you know that Burrowing Owls are the only species of owls nesting and roosting in underground burrows? In the Bay Area, these birds rely mostly on California ground squirrels to dig these burrows. When ground squirrels are absent, artificial burrows are sometimes installed as a temporary management tool.

Burrowing Owl populations have been declining throughout most of their range. Some factors for the decline include destruction of grassland habitat, lack of vegetation management, lack of prey, predation, and ground squirrel extermination. Ground squirrels are a keystone species for healthy grassland habitat and provide important ecosystem services. SFBBO collaborates with Santa Clara Valley Audubon Society to conduct vegetation management for Burrowing Owl habitat. We hope to resume volunteer work days in the future, so keep an eye out! Thank you to Phil Higgins and Sandra Menzel for being our guest scientists and answering these questions. |

|

Mono lake

|

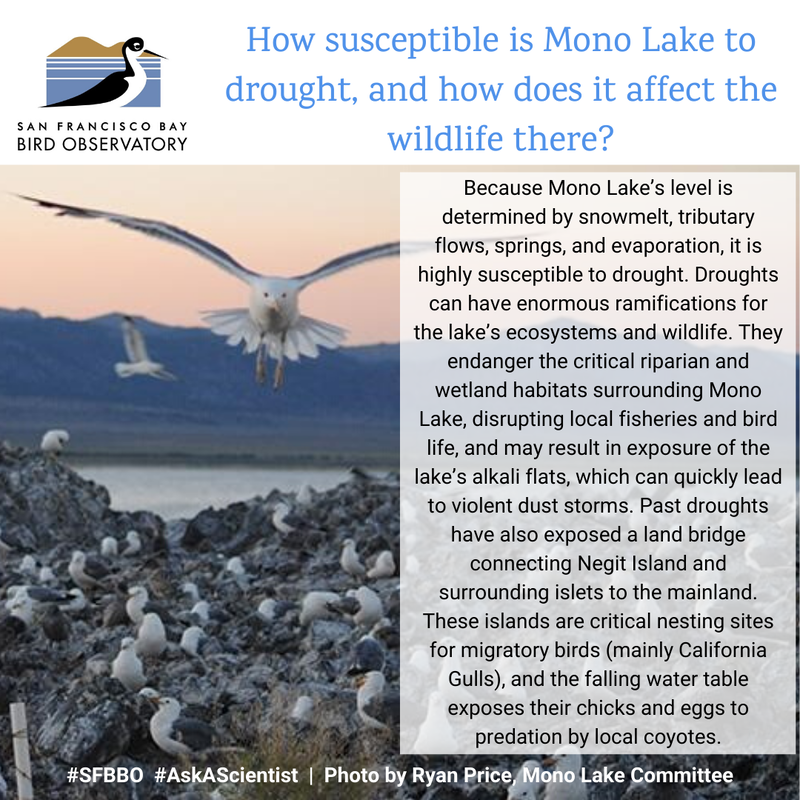

Mono Lake is a “terminal”, or one with no outlet. This means its level is determined solely by tributary inflows, precipitation, and evaporation, and makes it highly susceptible to disruptions. As a naturally hypersaline lake, it is also an essential stop for migratory birds traveling across the Great Basin and along the Pacific Flyway.

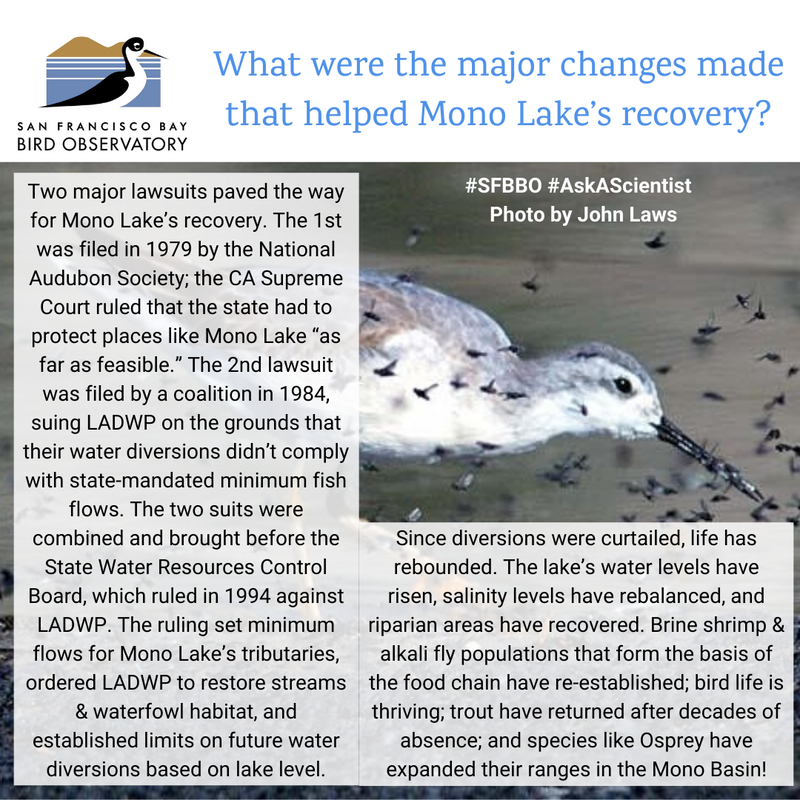

In 1941, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) began diverting water from the lake’s tributaries, resulting in severe ecosystem disruptions. In 1994, after decades of protest, research, and legal battles, the LADWP was forced to curtail its diversions and outline plans for local restoration, conservation, and monitoring programs. Many species at Mono Lake have since made spectacular recoveries, and the basin remains one of the most important birding hotspots in California. Mono Lake’s most iconic natural landmark is its eerie, crumbling tufa towers! How are these bizarre structures formed? Where freshwater springs percolate through the lake’s naturally saline water and volcanically-enriched sediments, calcium in the freshwater combines with carbonate in the saline water. The resulting mix solidifies as the minerals age, ultimately forming tufa towers that can reach over 30 feet! Tufa can also form via biogenesis, through the biological activity of organisms like the alkali fly. When an adult alkali fly emerges from its underwater pupae case, it leaves behind a tiny deposit of calcium carbonate that contributes (on a minute scale) to the growth of underwater tufa towers. |

Thanks to SFBBO Science Outreach Intern Charlotte Diamant for answering these questions. She spent a semester researching the human and natural history of this remote alkaline lake located east of Yosemite National Park and near the Nevada border.

|

Butterflies

|

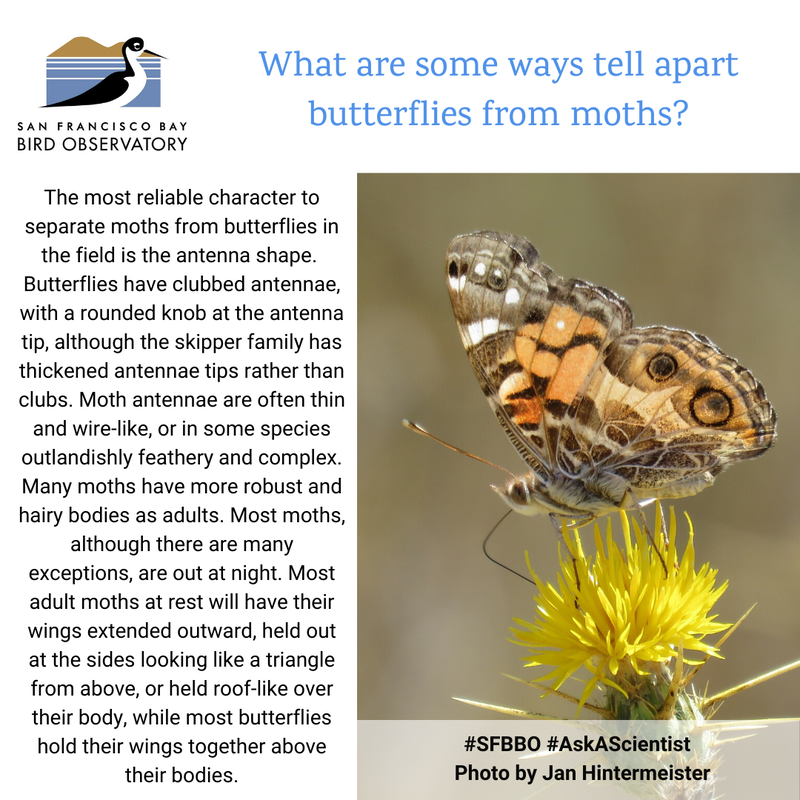

Butterflies are in the major insect order Lepidoptera, which contains butterflies and moths. Lepidoptera means “scaled wings”; wings are covered by tiny overlapping scales whose pigment and structure provide the colors that we enjoy. Butterflies are just a single branch of this large group. The number of moth species is about 15 times the number of butterflies, so many naturalists think of butterflies as a small group of colorful day-flying moths.

Butterflies have four distinct life stages: egg, larva (caterpillar), pupa, and flying adult. The stage that has the largest impact on the environment is the caterpillar, often called an “eating machine,” accumulating stores of proteins and fats that fuel metamorphosis. As a bag of nutrients, the caterpillar is a high-energy food source for birds and other animals, particularly parasitic wasps. Adult butterflies can be easy to see as they fly through our neighborhoods and wild lands. Caterpillars are often seen by chance, although in the Bay Area, Variable Checkerspot caterpillars can often be found on a very common host plant, Sticky Monkeyflower, in the spring. In general, pupae are rarely seen because they are often well-camouflaged and don’t move. Even though eggs are very tiny pinhead-sized objects, with effort they can be located by looking for egg-laying behavior. Adult butterflies often will perch on plants for long time periods or fly from flower to flower sipping nectar. A female butterfly that flies from plant to plant, spending a few seconds and moving on but not nectaring, may be laying eggs that can be seen by carefully searching. |

Thanks to SFBBO Board member and volunteer Jan Hintermeister for answering these questions. He has watched butterflies and led butterfly hikes for 10 years. Why would someone interested in birds care about butterflies? On warm sunny afternoons when bird activity can be subdued, butterflies are at their peak. Many are easy to see and identify with colors that easily rival those of warblers, orioles, or tanagers. Butterfly caterpillars can be an important food source, particularly during the breeding season when even seed-eating birds turn to caterpillars to feed their young.

|

Bacteria

|

Today, there is a significant fear of these little bugs. It is important to understand that every single creature on our planet, including humans, depends on these single-cell organisms to survive and thrive. They are responsible for helping digest our food, strengthen our immune system, and even producing hormones. Our mood, health, and overall well-being depends on a delicate balance between pathogenic (bad) and beneficial bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Learning more about their mysterious world has led humans to fascinating discoveries and we are just scratching the surface in our understanding.

Did you know:

|

Thank you to SFBBO Board Member Anastasia Neddersen for answering these questions.

|

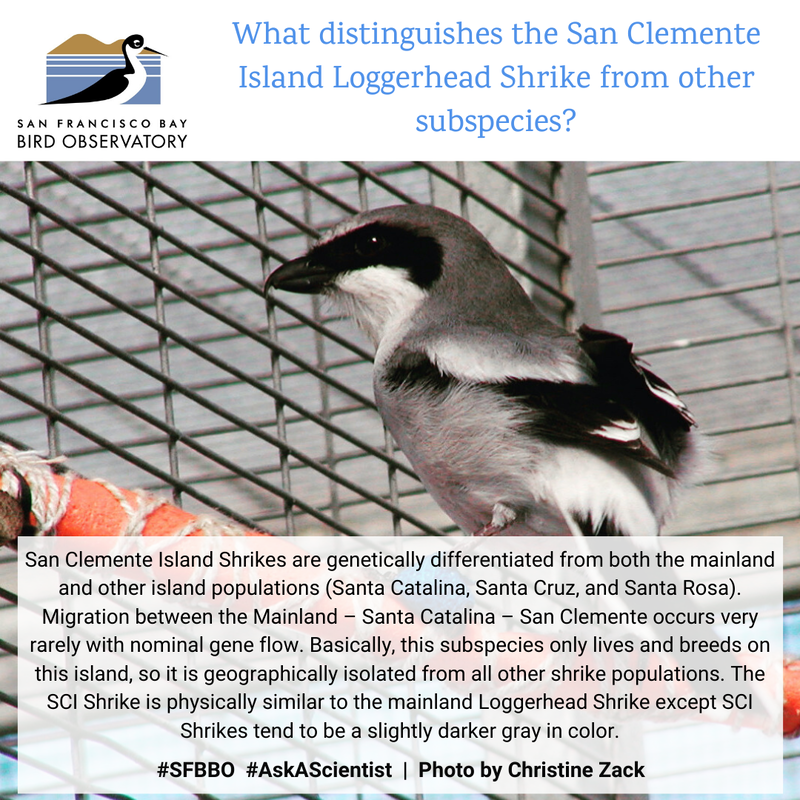

San clemente island loggerhead shrike

|

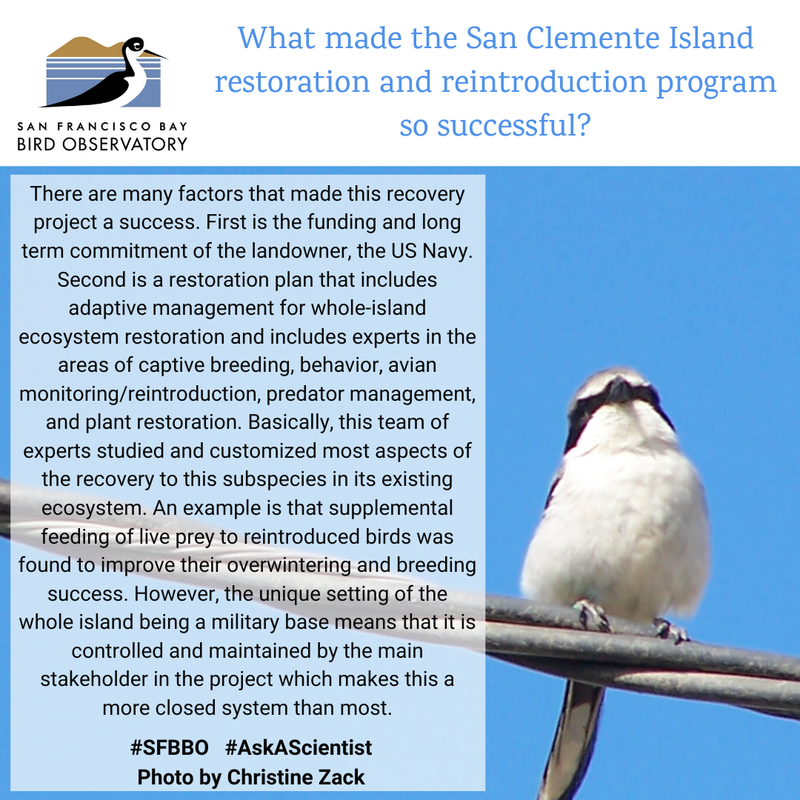

The San Clemente Island Loggerhead Shrike is an endangered subspecies endemic to the most southern Channel Island of California. Since the 1980s, the US Navy has been working to recover this subspecies and restore the island ecosystem which includes other threatened & endangered species.

Loggerhead Shrikes are often called the “butcherbird” because they impale their prey on cacti or branches. This behavior is called caching. They wedge their food in the fork of branches to break up and eat prey that is almost as large as they are. It also allows them to store larger prey items to eat over a few days or feed to their chicks. Smaller food items like crickets might be impaled on barbed wire for morning snacks. Watching a shrike kill a mouse or lizard is an art. Male shrikes demonstrate how to capture, kill, and cache mice for their juveniles. They learn to fly down, grab prey, and shake it just right to paralyze it and break its neck, and that prey can only be cached if it isn’t moving. Practice makes perfect for these tiny carnivorous birds! |

Thanks to SFBBO board member Christine Zack for answering these questions. She spent 3+ years studying the captive breeding behaviors of these shrikes. This captive breeding and reintroduction project is one of the most successful avian restoration projects to date!

|

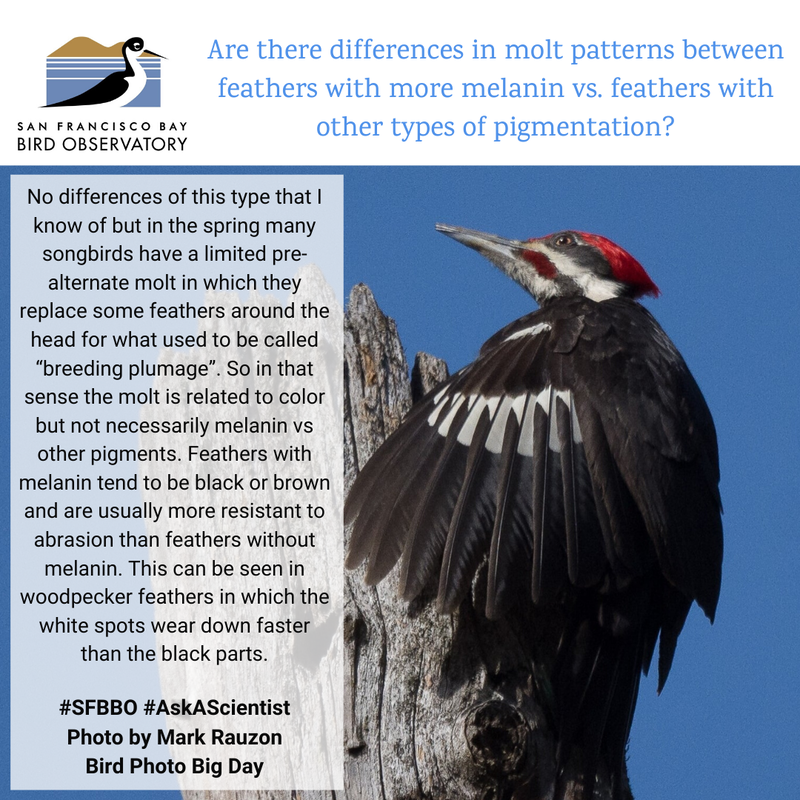

Feather molt

|

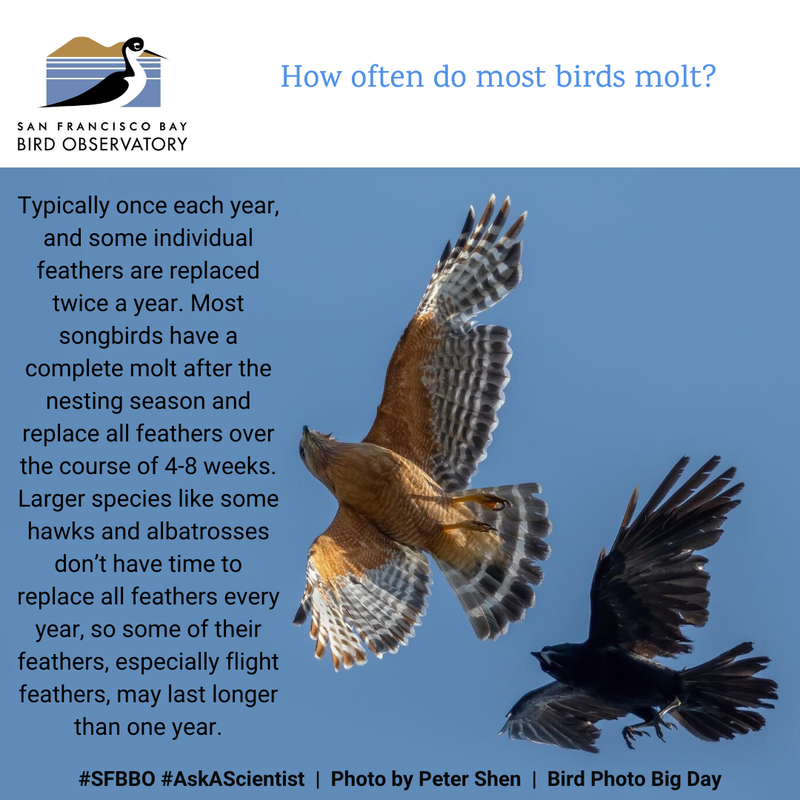

Feathers are a defining feature of modern birds and serve many functions including flight, insulation, camouflage, and display.

Because feathers are so important, they need to be replaced typically once each year depending on the bird species and particular feather. The process of feather replacement is called molt. In the left photo, notice the very worn primary (outer edge) feathers of the Nashville Warbler and the new feathers coming in. In the middle photo, compare the fresh feathers of the hatch year Audubon's Warbler to the worn feathers of the adult (right photo)! In most temperate-zone songbirds, adults molt after the breeding season in late summer and fall. Some species even migrate to a specific place to complete the molt before continuing migration. This is called molt migration, and it's apparently more common for species in western than in eastern North America. One example of molt migration is of Orange-crowned and Nashville Warblers migrating to high elevation meadows in the Sierra Nevada for a few weeks before continuing south to Mexico!

Left: Hatch-year Orange-crowned Warblers move up to higher elevation meadows in the Sierras to molt all the body feathers, including the greater wing coverts as shown here, but usually no flight feathers. Right: Bad hair day for an Orange-crowned Warbler. This happens when they molt many of the body feathers simultaneously. |

Thanks to SFBBO Lead Biologist Dan Wenny for answering these questions.

|

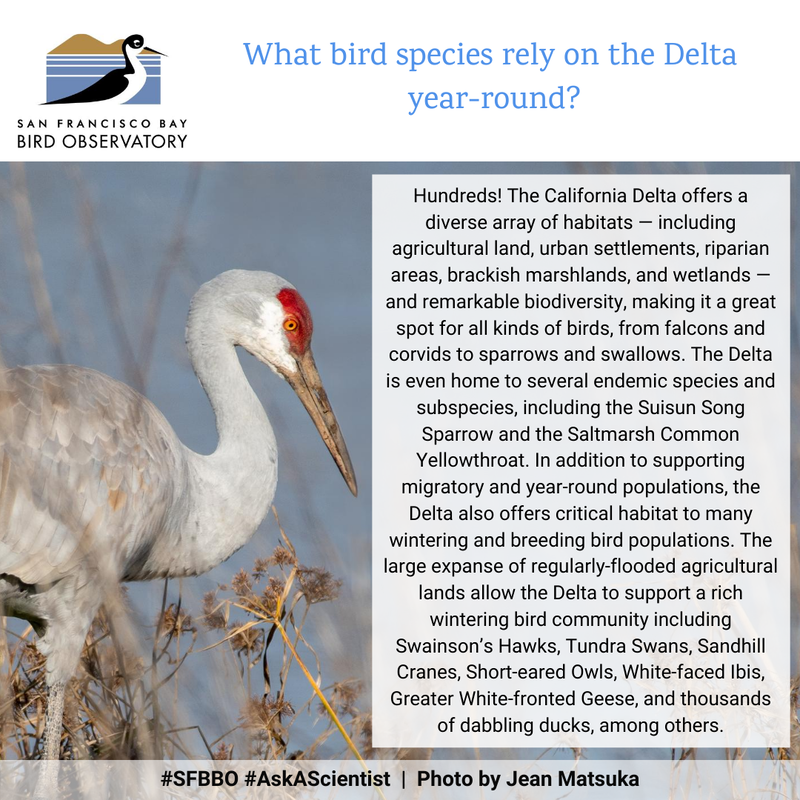

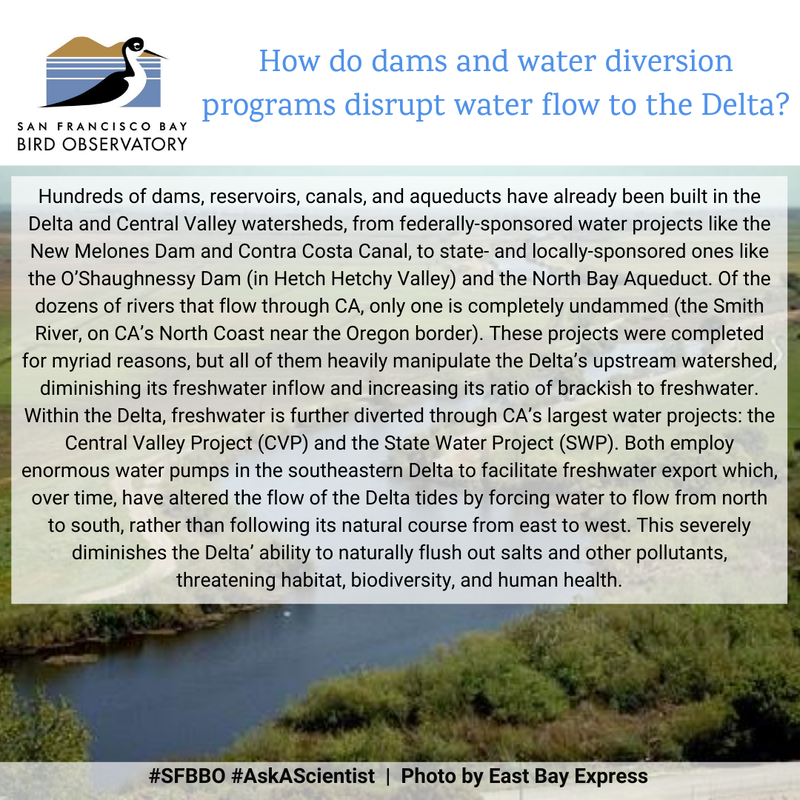

California delta hypersalinity

|

The California Delta extends over 1,000 square miles from the western edge of the Central Valley to Suisun Bay, where the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers join the greater SF Bay. As one of the largest estuaries in N. America, the Delta is a key stop for migratory birds traveling the Pacific Flyway and provides habitat for hundreds of species, including many endemic and endangered populations.

But the Delta is also threatened by land reclamation, agricultural practices, water diversions, and urban growth—all of which have disturbed its delicate balance of fresh- to brackish water. Dams, levees, and water diversions have steadily decreased the delta’s freshwater inflow, increasing the ratio of brackish to freshwater and diminishing the ability of the Delta tides to flush out salts and pollutants. This has significant consequences for the environment, economy, and public health, impacting both humans and the natural world. The Delta has 5 major freshwater tributaries—the Sacramento, San Joaquin, Mokelumne, Cosumnes, and Calaveras rivers—which account for nearly half of the annual snowmelt and runoff in all of California. As these waterways move west towards the SF Bay, they mix with salt water from the Pacific Ocean, creating a delicate balance of saline and freshwater that forms the basis for healthy marsh habitats and biodiversity. When this balance is disrupted, hypersalinity “hotspots” emerge, as salts settle in narrow Delta channels without sufficient drainage. Some salts can even be drawn into pumps and transported farther inland to areas less adapted to salt-intrusion—like the San Joaquin and Tulare Lake Basins—where hypersalinity poses an even more severe ecosystem threat. |

Thanks to SFBBO Science Outreach Intern Charlotte Diamant for answering these questions.

|

Marbled murrelets

|

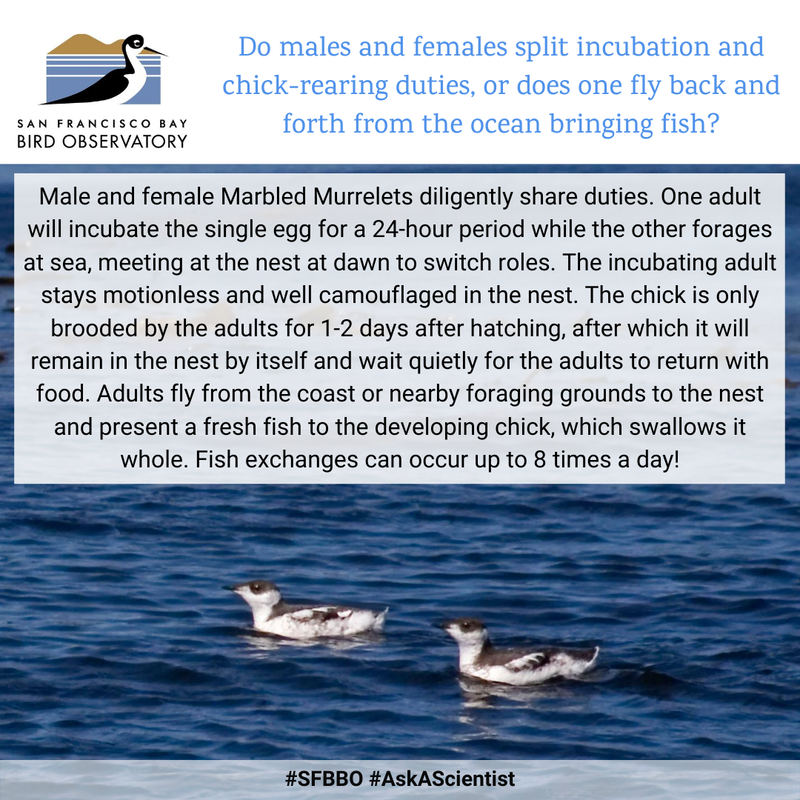

Marbled Murrelets are endangered seabirds that spend most of their time in marine environments, but they rely on old growth redwood and Douglas fir forests to breed in California.

They don’t really build nests; they just lay their egg in a depression of mossy material on a flat platform created by a large branch. This is why large mature trees are important habitat for the species. They only lay one egg per nest, and typically only lay one nest per year. There’s a lot invested in that single egg, so it’s incredibly important to protect every nest in our area! The Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District protects Marbled Murrelets by maintaining mature forest so these birds have habitat to breed in and by restricting activities that cause disturbance and noise during their breeding season. Midpen scientists also conduct audio-visual surveys and use Acoustic Recording Units to detect where murrelets are in the preserves and which flyways they might be using. Thank you to guest scientist Karine Tokatlian for answering these questions. |

How can you help? If you visit Midpen Preserves with murrelet habitat (Purisima Creek Redwoods OSP, El Corte de Madera OSP, and portions of La Honda Creek OSP), remember to pack out your trash and food scraps!

|

Bird-building collisions

|

Collisions with buildings are estimated to cause up to 1 billion bird deaths each year in the US. The main reason birds fly into buildings is glass: glass can act as mirrors, reflecting the sky and trees, and may appear to many birds as continuous habitat. Transparent windows can also appear to be clear pathways for birds to fly through, especially when habitat is visible on the other side. For these reasons, glass near vegetation is especially dangerous, and artificial light at night worsens the problem by drawing birds near buildings.

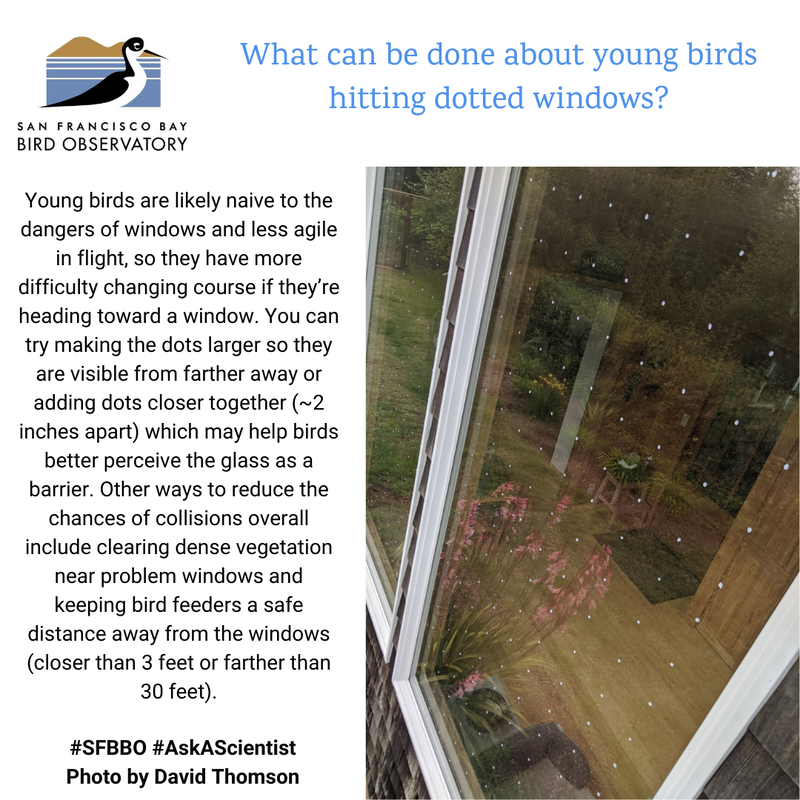

Some birds are more vulnerable to collisions with buildings than others. Most victims of collisions are nocturnally migrating birds, such as warblers, flycatchers, and sparrows, but other birds like hummingbirds are also vulnerable. Recent research shows that forest birds and insect-eating migrants are especially susceptible to collisions. As many of these species are in decline for a variety of reasons, a great way to help birds is by making windows more visible, such as by using fritted glass or applying patterns to glass. |

Thanks to SFBBO Biologist Anqi Chen and Environmental Education & Outreach Specialist Sirena Lao for answering these questions.

|

Polar bears

|

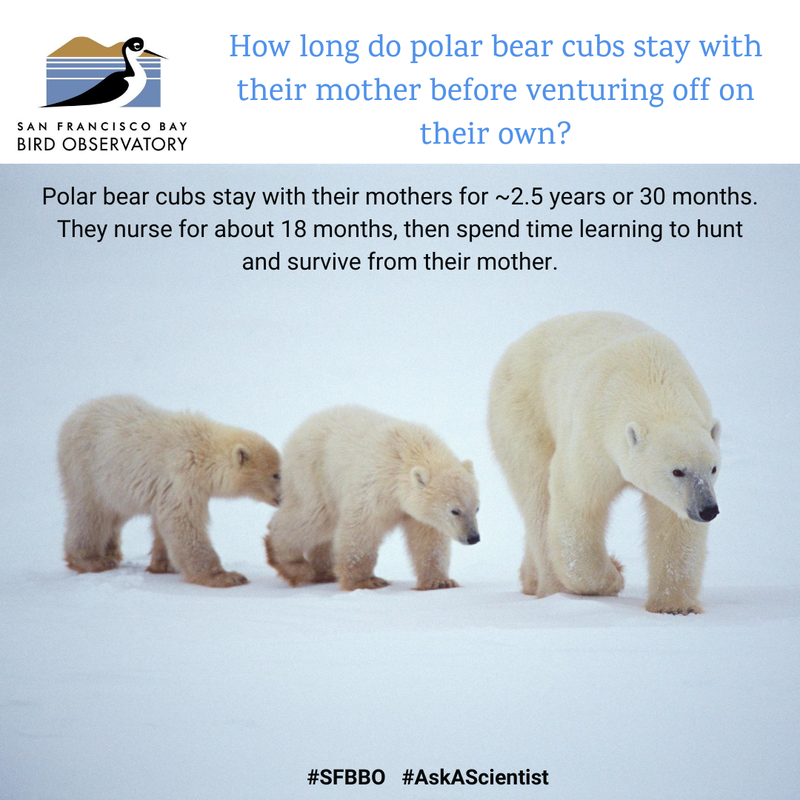

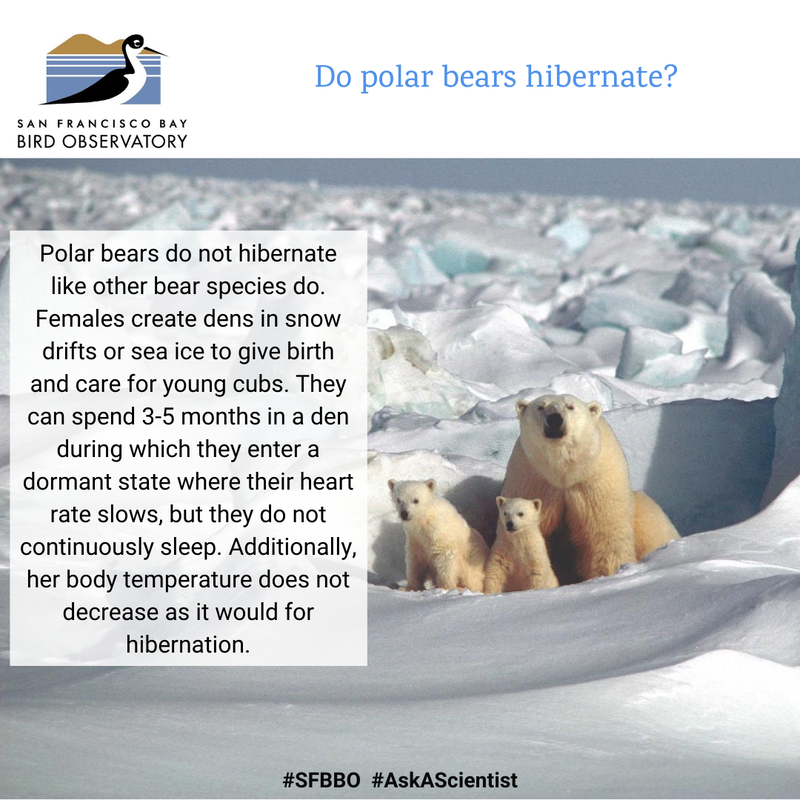

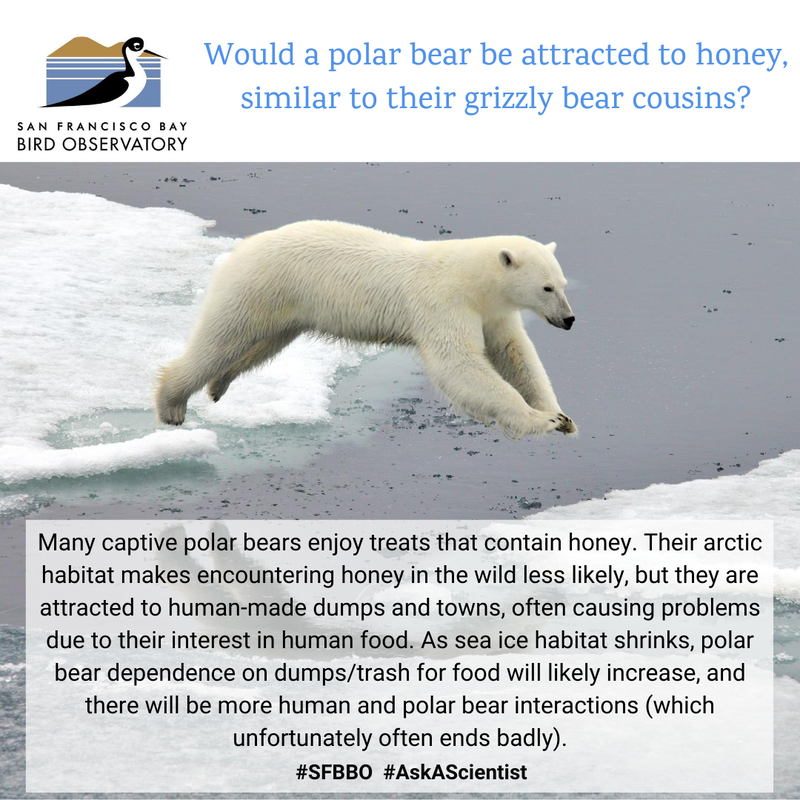

Polar bears are solitary but often communicate through scent as they have an amazingly well-developed sense of smell. Most bears have stable, established home ranges and use trees or other substrates to mark their territories and signal their availability to mate. However, polar bears can have a home range of 50,000 square miles, which changes year to year with sea ice formation. Their habitat is mostly snow and ice without trees and rocks to mark. So how do they find each other in this vast space to mate? It’s all in the feet and their tracks as they walk!

On average, female polar bears mate every 3 years. Ovulation is induced by mating. They have delayed implantation, which means they mate in spring but the embryo doesn’t grow until fall when she enters a maternity den. This also allows polar bears to mate, den, and give birth during times of year that are optimal for survival. Polar bears have been observed sniffing tracks in snow and ice and following them for hundreds of miles to find a mate. Christine’s captive research showed that, using pedal scents, polar bears can distinguish between male and female bears as well as females in estrus versus those with cubs. |

Thanks to SFBBO Board Member Christine Zack for answering these questions. She studied olfactory communication of polar bears via comparative captive tests for her Master’s while working for the San Diego Zoo’s Institute for Conservation.

|

Birding by ear

|

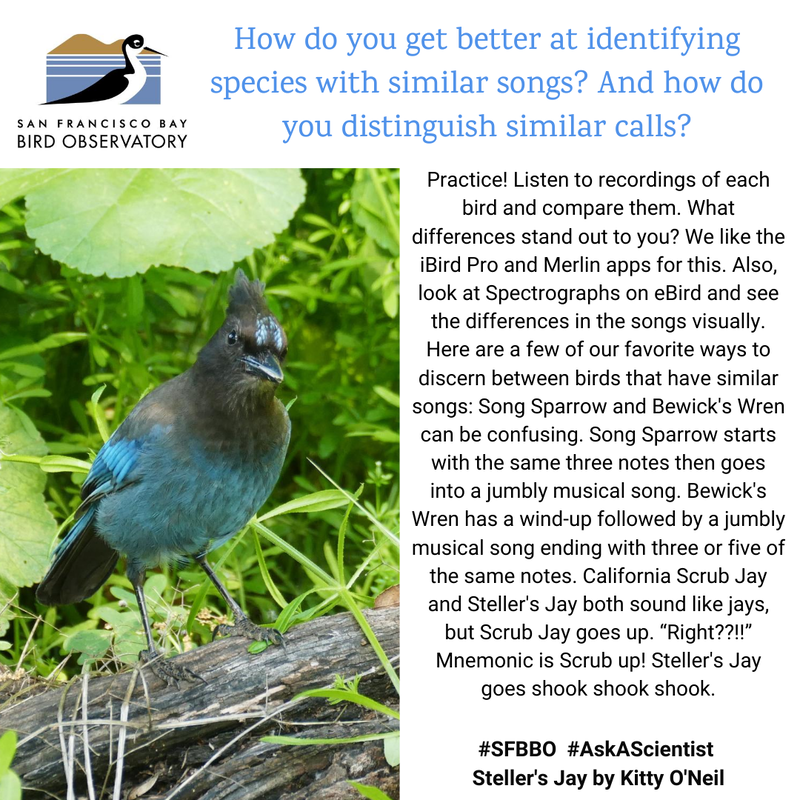

Birding by ear is a great way to find, identify, and understand the birds around us. Birds have two main types of vocalizations: songs and calls. Birds sing their full songs mostly in spring, during the breeding season. A bird's song can be sweet, melodic, and long like an American Robin or it can be sharp and shrill like the kon-ka-ree of a Red-winged Blackbird. Birds use shorter calls, often just a "chip", throughout the year to make contact with each other, sound an alarm that a predator is about, or communicate an individual's location.

And vocalizations aren’t the only way we identify birds by ear. Birds make other recognizable sounds, such as the drumming of a Pileated Woodpecker as it fades in intensity, the toe-to-leaf scratching of a Spotted Towhee, the tail feather popping sound of an Anna's Hummingbird, and the whistling wing noise of a Mourning Dove. Birding by ear is a great way to find and identify hard to see birds like owls, rails, Wrentit and Horned Lark. And in some cases, vocalizations are the best way to distinguish two species, such as Eastern vs. Western Meadowlark. The best way to start learning to bird by ear is to listen to the sounds of the birds you see each day, like the Black Phoebe. Some birds are born with innate songs, while others learn to sing from their parents and neighbors. And some birds go even further and learn the songs of other birds. These are referred to as mimics and they can be tricky for birding by ear! Steller’s Jays imitate Red-tailed Hawks, often very convincingly, to scare off other birds. European Starlings blend environmental sounds of goats, frogs, and traffic signals in with their own whistles and squeaks. But perhaps our best local mimic is the Northern Mockingbird. An adult male Mockingbird can string together up to 200 different songs, usually repeating each one many times before moving on to the next. We had a neighborhood Mockingbird who did a four-part car alarm that could barely be distinguished from the real thing! |

It is thought that the more songs a Mockingbird can remember and sing, the more appealing it is as a mate. If you’ve ever had a bird singing all night long in your neighborhood, it was probably a lonely male Mockingbird displaying its mimicry skills in hopes of making a love connection.

Thank you to guest scientists Kitty O'Neil and Bill Pelletier for answering these questions. |

soil

|

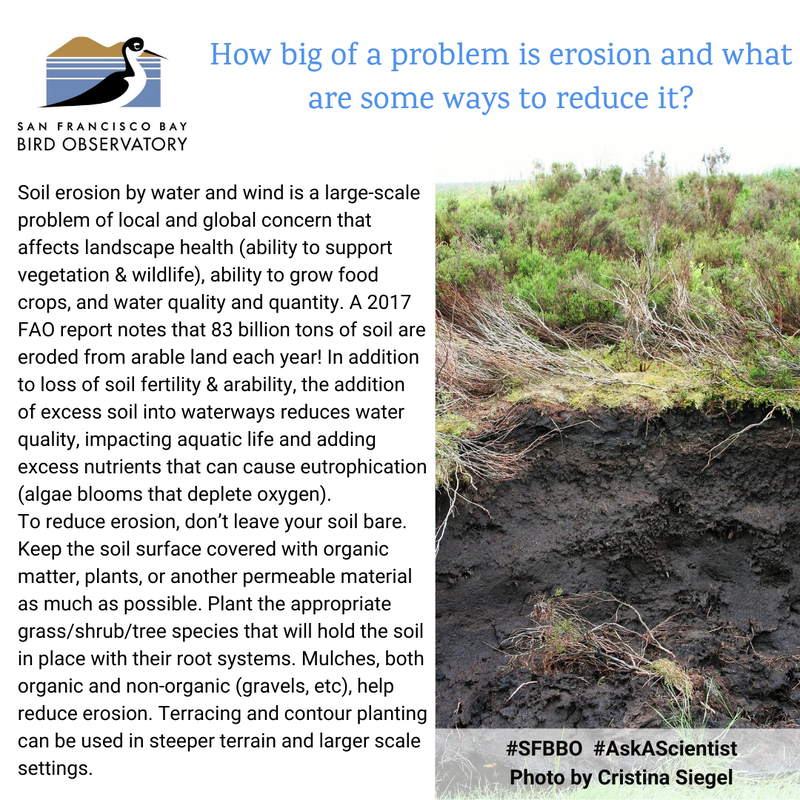

We often take the soil under our feet for granted, but soil is more than just a bunch of dirt! A key SFBBO effort is to restore habitats to support the local bird life we all love. Good restoration efforts begin with the soil. Soils are the place our food crops are grown, the support beneath our homes and businesses, the base for terrestrial plant life, a zone for cleansing and storing water, a critical medium for carbon and nitrogen cycles, and a home to wildlife such the Burrowing Owl. Some birds even need soil to get clean with a good roll in the dirt!

Soils are a key storage sink for some of the excess carbon in our atmosphere driving climate change, and they are the biologically active dynamic zone for supporting life. Did you know that a teaspoon of rich garden soil can contain up to one billion bacteria, several yards of fungal filaments, and several thousand protozoa? Soil can make you happy – literally! Scientists found that a soil bacterium (M. vaccae) triggers the same serotonin-releasing neurons in the brain as Prozac. Feeling down? Get out and commune with some soil! Soils come in all colors, from blue-green to brown to bright red. They can even develop in the canopy of massive redwoods. They are all ages, too; scientists recently found an ancient soil they estimate is 3.7 billion years old! Just like birds, soils are unique to their environment and have a classification system with common and scientific names too. |

Thanks to SFBBO Board Member Cristina Siegel for answering these questions. Cristina has worked on a High Sierra wilderness soil survey and as a USFS-Pacific Southwest Research Station soil scientist in Redding. Her research focused on soil compaction effects on tree growth, forest health, and soil-water-plant interactions

|

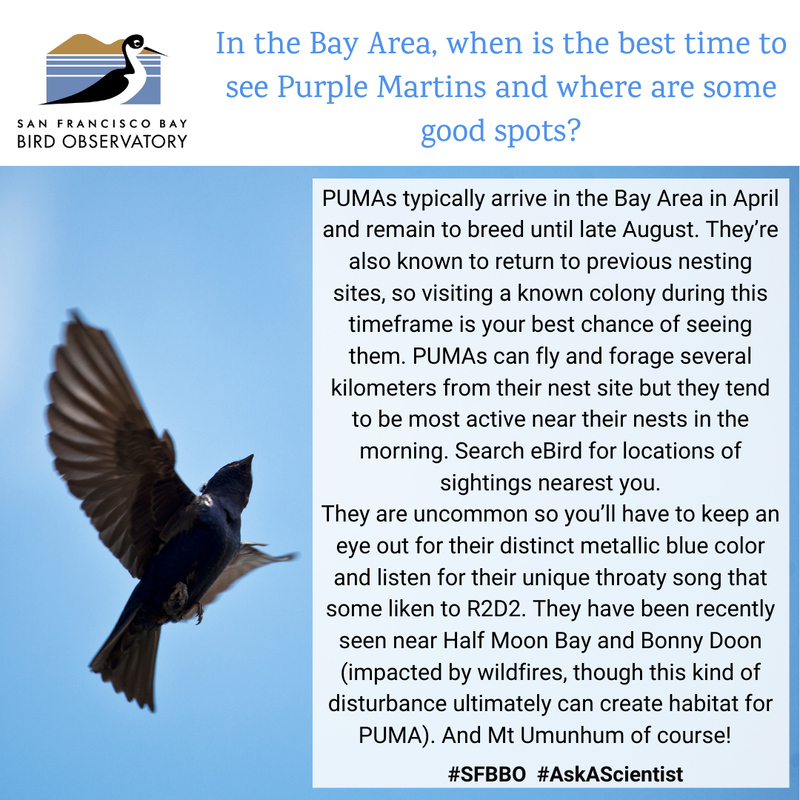

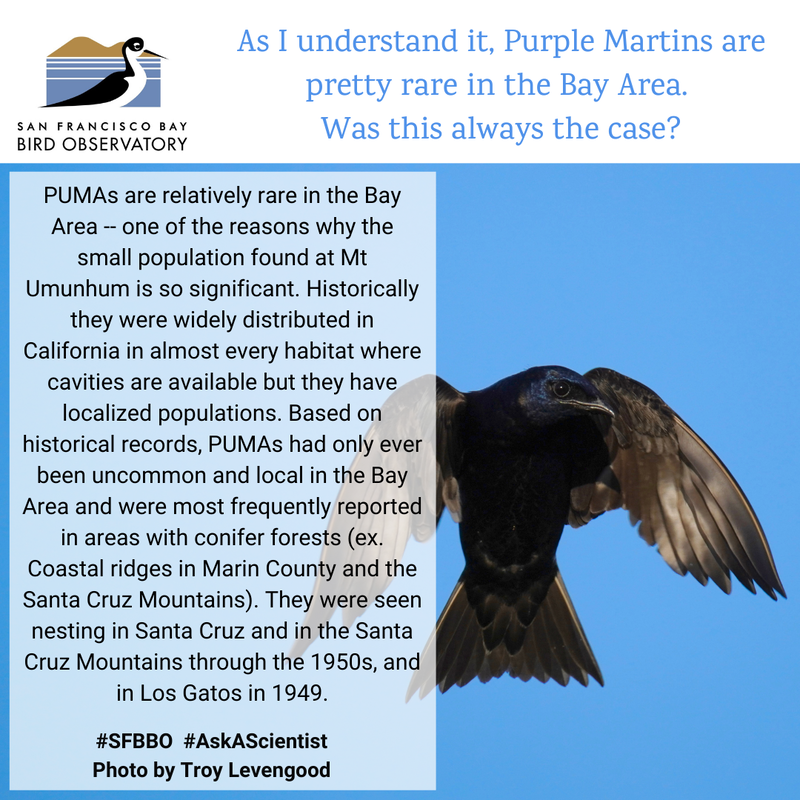

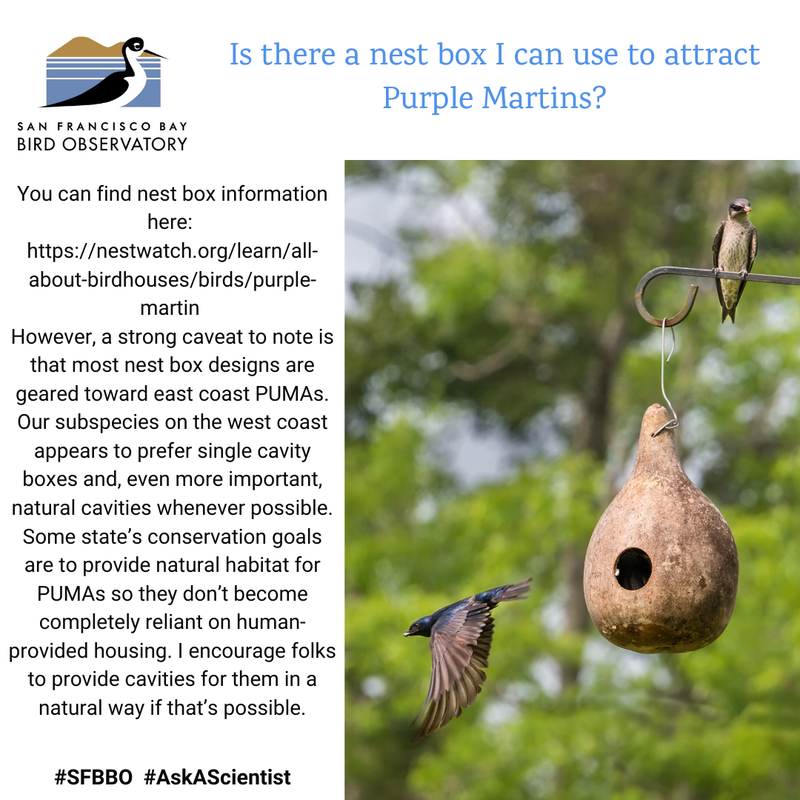

Purple martins

|

Purple Martins are the largest swallows in North America. They are more common on the east coast, but we have migratory and breeding populations in a narrow band here on the west coast. They are a Species of Special Concern in California due to declines in range and population size.

Purple Martins nest in cavities created by other species and also use birdhouses, gourds, or crevices of buildings or rocky cliffs. Native Americans would set up gourds for them, and birds began shifting to using artificial nest sites before colonization by Europeans. They have a long history of this co-habitation with humans, especially in eastern North America where almost all nest sites are provided by humans. In western North America, birdhouses and gourds seem less effective, and folks are encouraged to provide more natural habitats like tree snags and wooden poles. Eastern populations also prefer multi-compartment birdhouses, while western populations mostly use single-cavity houses, similar to those used by bluebirds and Tree Swallows. The Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District works to conserve Purple Martins; 5-6 were observed at Mt Thayer (adjacent to Mt Umunhum) in Midpen’s Sierra Azul Open Space Preserve, and they were confirmed breeding in cavities in old wooden telephone/electricity poles. Their presence at Mt Thayer confirms that the Mt Umunhum area is the most important site in the Santa Cruz Mountains for Purple Martins. |

Midpen scientists set up nest boxes in the area to provide more habitat for Purple Martins, but so far have found no evidence of them being used. They are working on setting up different types of bird boxes, hoping that a different design will be more attractive to them to support this important population.

Thank you to guest scientist Karine Tokatlian for answering these questions. |

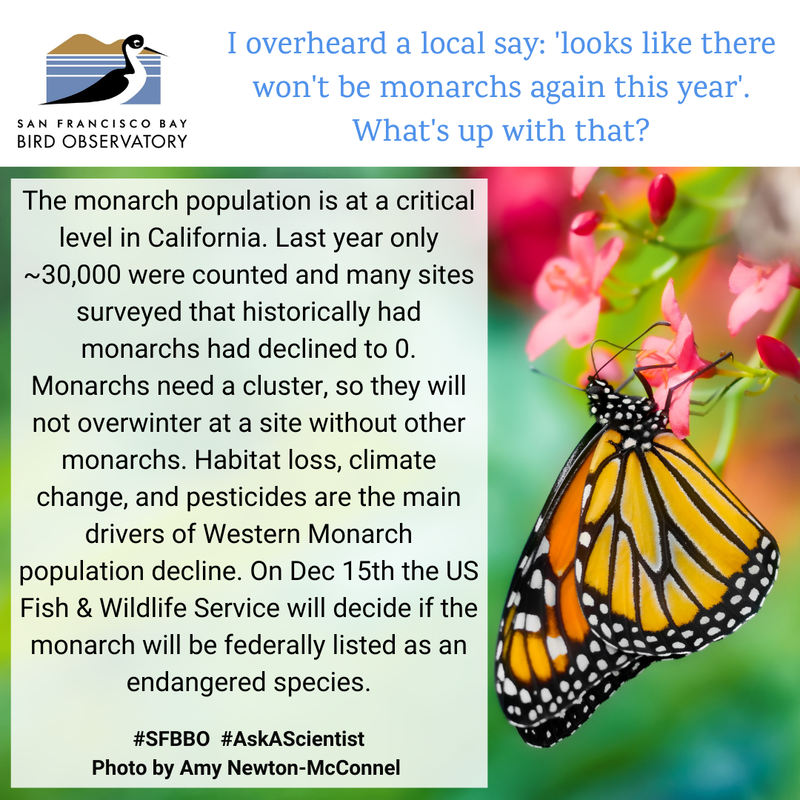

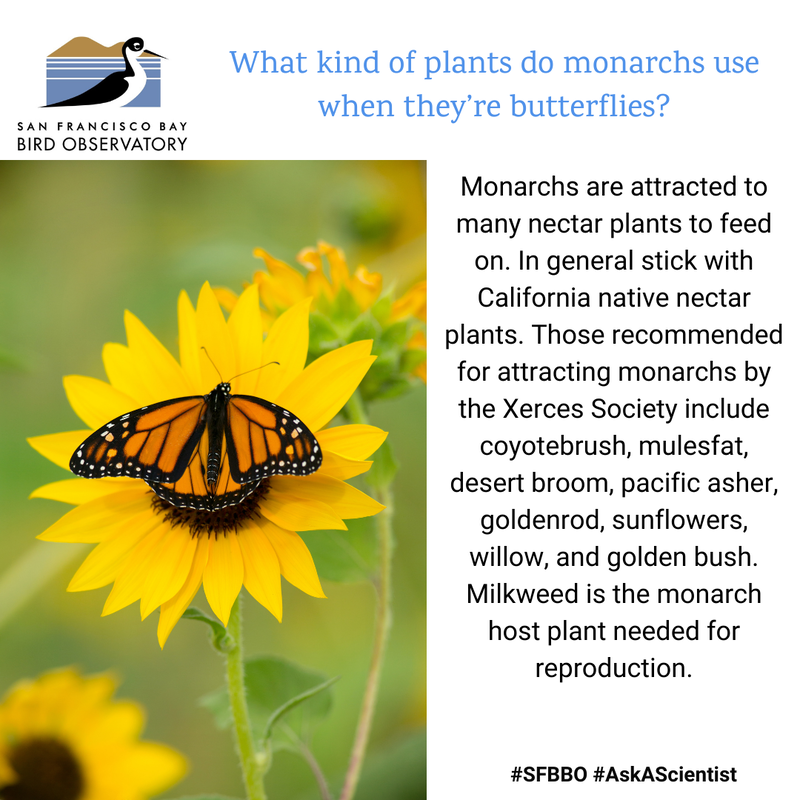

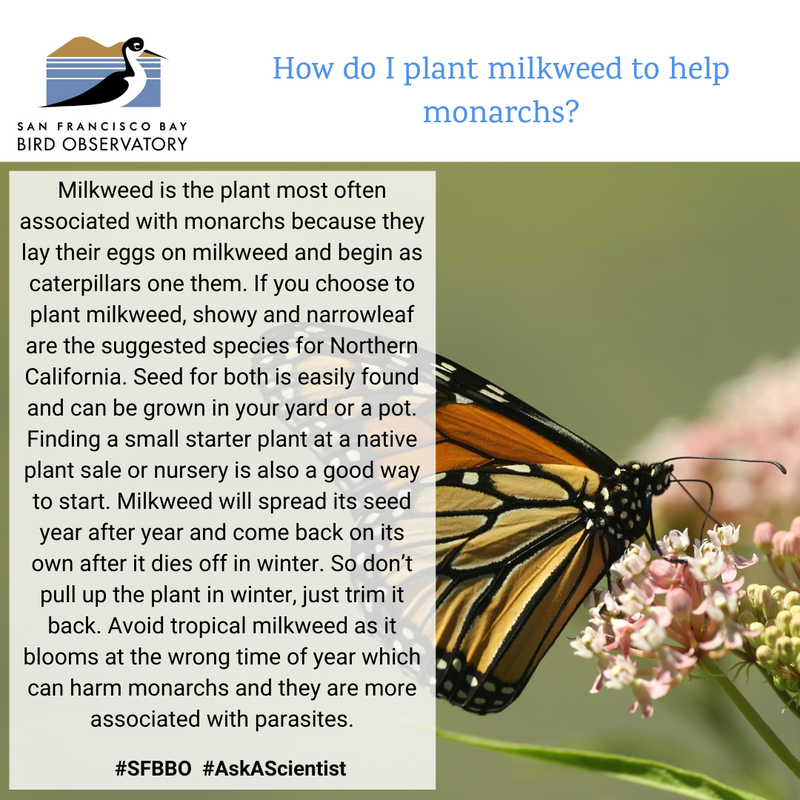

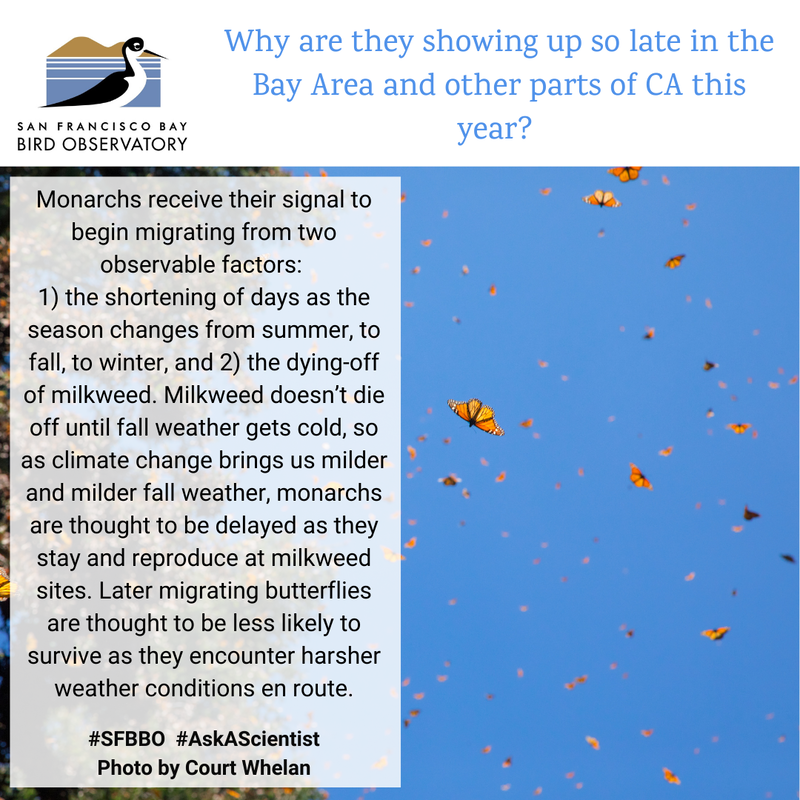

Monarch Butterflies

|

For several years, SFBBO board member Christine Zack has been a community scientist participating in the Monarch Thanksgiving and New Year's counts in partnership with The Xerces Society, Monarch Joint Venture, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. This year, the Western Monarch Count Thanksgiving Count runs from Saturday, November 14 to Sunday, December 6. The New Year's Count runs from Saturday, December 26 to Sunday, January 10. These counts document overwintering monarchs at 240 sites along the coast of California this fall. Citizen scientists attend a training, are assigned a site, and record data via an app. Christine also participated in the migrating monarch and milkweed surveys at Don Edwards SF Bay National Wildlife Refuge in Alviso and Lake Cunningham, which help determine habitat availability and usage in California.

Historically, an estimated 4.5 million monarchs overwintered on the California coast. 2018 & 2019 counts were substantially lower than even just 2-3 years prior, when the population was ~200,000-300,000 butterflies. Volunteers reported 29,418 monarchs in 2019—less than 1% of the population in the 1980s. The number of overwintering monarchs in California continues to be ~30,000 monarchs—the minimum threshold estimate below which the population may collapse. Want to help monarchs? Check out the The Xerces Society's Western Monarch Call to Action and This is How You Can Help document. These actions will benefit monarchs and also support our many other native bees and butterflies—and birds! |

Thanks to SFBBO board member Christine Zack for answering these questions.

|

This program was possible thanks to a grant from the Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District.